Third-Party Dependency Management: A Developer's Guide

When Log4Shell dropped in December 2021, I watched teams scramble to answer a single question: "Are we affected?" Some teams had the answer in minutes. Most didn't. They spent days manually checking dependency trees, grepping through lockfiles, pinging Slack channels asking who used what. The difference between those two groups came down to one thing - whether they had third-party dependency management in place. That experience made it clear to me that SBOMs aren't just a compliance checkbox. They're a practical engineering tool that pays for itself the first time something goes wrong.

What Is an SBOM?

A Software Bill of Materials is exactly what it sounds like - a list of everything your software is made of. Think of it like the ingredients list on packaged food. It tells you every library, framework, and dependency your application uses, along with version numbers, licenses, and where each component came from.

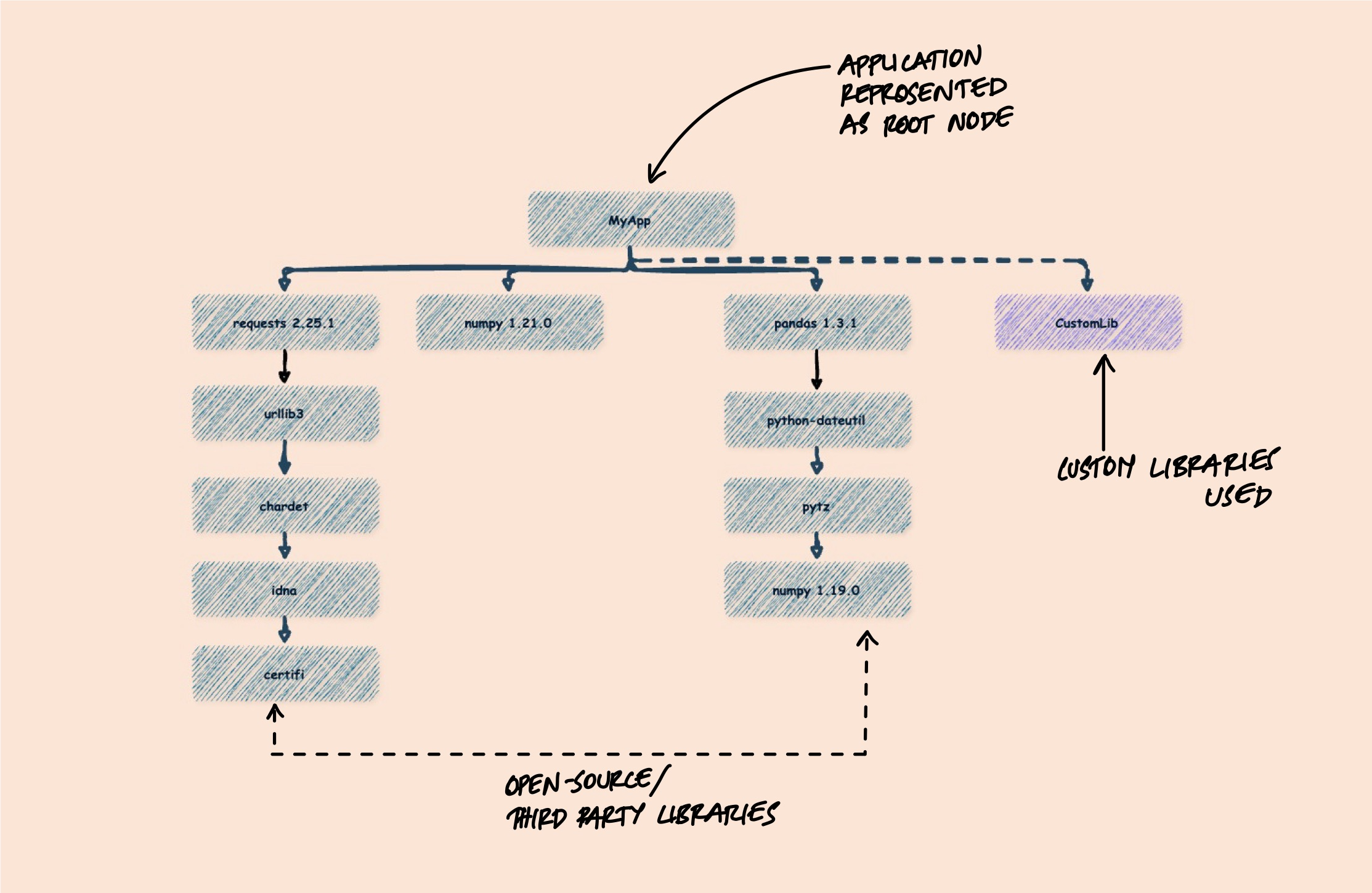

But the interesting part isn't the direct dependencies you chose - it's the transitive ones you inherited. When you add requests to your Python project, you also get urllib3, certifi, charset-normalizer, and idna. When you add pandas, you get numpy, python-dateutil, and pytz. A typical application might declare 20 direct dependencies but actually contain 200+ components when you trace the full tree.

An SBOM captures this full picture - not just what you installed, but everything that came along for the ride. And that distinction is what makes it useful. The vulnerabilities and license issues that bite you are almost always in transitive dependencies you never explicitly chose.

Why SBOMs Matter

The Log4Shell Wake-Up Call

The strongest case for SBOMs comes from what happens when you don't have one.

In December 2021, a critical vulnerability (CVE-2021-44228) was discovered in Log4j, a ubiquitous Java logging library. It scored a perfect 10.0 on the CVSS severity scale - an attacker could execute arbitrary code on any server running the affected version, just by sending a specially crafted string.

The vulnerability itself was severe. But the real problem was figuring out where Log4j was. It wasn't just in applications that directly depended on it - it was buried three, four, five levels deep in dependency trees. An application using Spring Framework used Spring Boot, which used Spring Boot Starter Logging, which used Log4j. You wouldn't see it in your pom.xml or package.json, but it was there.

Organizations with SBOMs could query their inventory and have a complete list of affected applications within hours. Everyone else was searching manually - and many didn't find everything.

# SBOM query result — finding every app affected by Log4Shell

# This is what teams WITH an SBOM could answer in minutes

Component: org.apache.logging.log4j:log4j-core

Vulnerable: v2.0 – v2.17.0

CVE: CVE-2021-44228 (Log4Shell)

CVSS: 10.0 (Critical)

Affected applications:

├── payment-service v2.14.1 (direct dependency)

├── order-api v2.11.0 (via spring-boot-starter-logging)

├── analytics-pipeline v2.16.0 (via kafka-clients → log4j)

└── auth-gateway v2.14.1 (via elasticsearch-rest-client)Regulations Are Making This Mandatory

Log4Shell was the event that moved SBOMs from "nice to have" to "required." Governments and industry bodies worldwide now mandate software component transparency - with real penalties for non-compliance.

US Executive Order 14028 (2021) requires vendors selling software to the federal government to provide an SBOM. There's no direct fine, but non-compliance means losing federal contracts - and potential debarment from future procurement.

EU Cyber Resilience Act (2024, fully enforced by December 2027) goes further. Manufacturers of any product with digital elements sold in the EU must generate and maintain a machine-readable SBOM. Penalties reach up to EUR 15 million or 2.5% of global annual turnover. Authorities can also withdraw non-compliant products from the market entirely.

EU NIS2 Directive (effective October 2024) requires essential and important entities to implement supply chain security measures - including tracking software components from suppliers. Penalties reach EUR 10 million or 2% of turnover, and executives can face personal liability.

In regulated industries, the requirements are even more specific. The FDA now requires SBOMs for medical device premarket submissions - without one, your device simply won't get approved. PCI DSS 4.0 (mandatory since March 2025) requires a complete inventory of all third-party software components in payment systems. DORA (effective January 2025) requires financial institutions in the EU to track all ICT dependencies, including open-source libraries.

What Organizations Do to Comply

In practice, compliance means building dependency management into your development workflow rather than treating it as a separate audit exercise. Most organizations that take this seriously end up doing some combination of the following:

- SBOM generation in CI/CD: Every build produces a signed, versioned SBOM alongside the artifact. Not a one-time scan - a continuous process.

- SCA tooling with policy gates: Builds fail automatically if a prohibited license or a critical unpatched CVE is detected. No manual review needed for clear violations.

- Vendor SBOM requirements: Procurement contracts require vendors to deliver machine-readable SBOMs with each release. Those SBOMs get ingested into the same vulnerability management platform as internally generated ones.

- Vulnerability response SLAs: Defined remediation timelines based on severity - critical within 72 hours, high within 7 days, medium within 30 days. The SBOM makes it possible to identify affected applications the moment a new CVE is published.

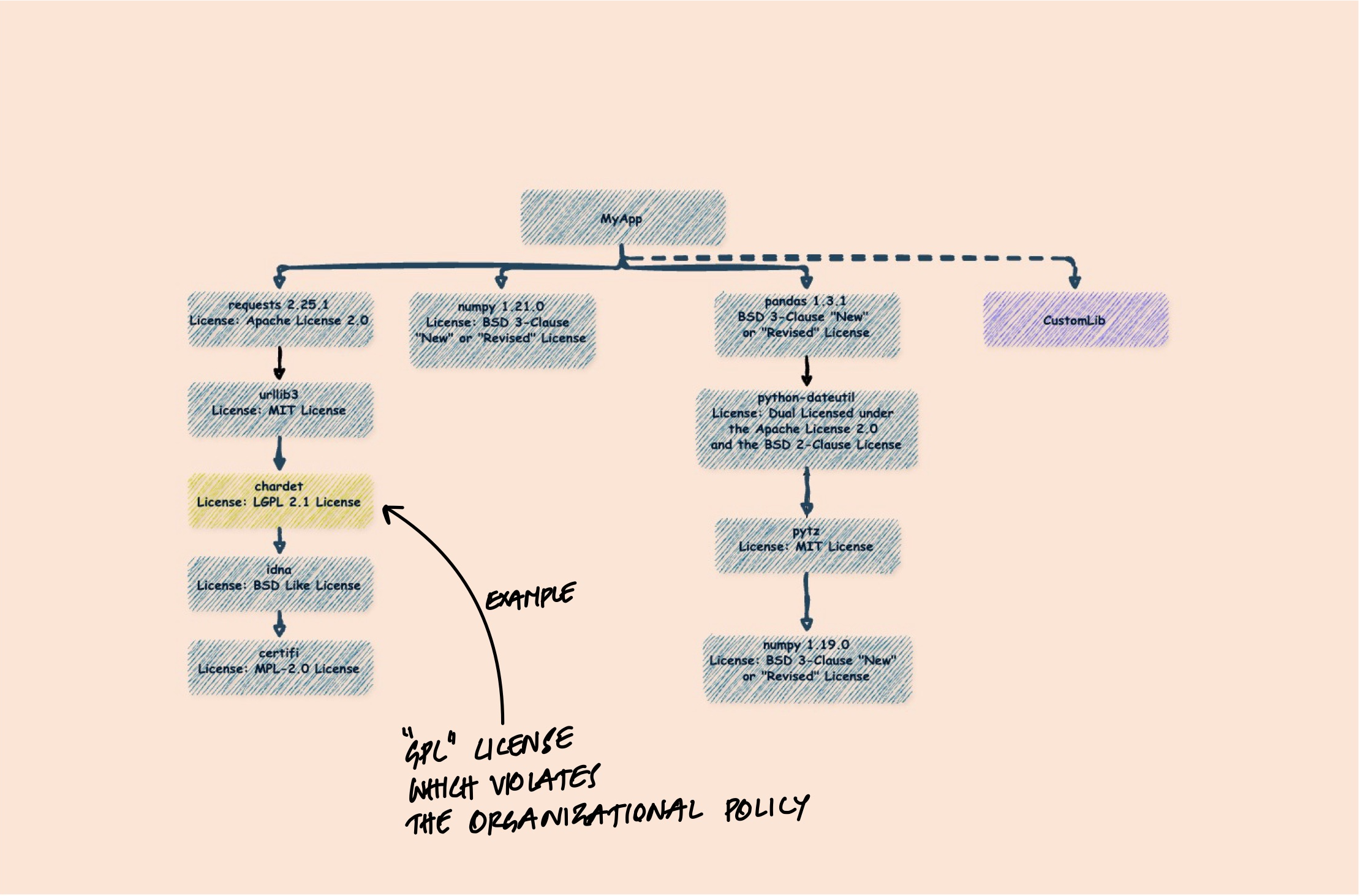

- License allow-lists: An organizational policy defining which licenses are approved (MIT, Apache 2.0, BSD), restricted (LGPL), or prohibited (GPL, AGPL) - enforced automatically during builds.

License Compliance

Security gets the headlines, but license compliance is where SBOMs quietly save you from expensive problems.

Open-source licenses come with obligations. MIT and Apache 2.0 are permissive - you can use them in commercial software with minimal requirements. But GPL licenses require that any software linking to GPL code must also be distributed under GPL. If you're building proprietary software and a transitive dependency pulls in a GPL library, you have a potential legal problem.

The tricky part is that this can happen without you noticing. You add a library with a permissive license, but one of its dependencies deep in the tree uses GPL. Without an SBOM that tracks licenses through the full dependency chain, you might not discover this until legal review - or worse, after release.

Incident Response

When a breach happens, the first question is "what's affected?" An SBOM turns this from a days-long investigation into a database query. You can immediately identify which applications use the compromised component, which versions they're running, and which environments they're deployed in. The difference between patching within hours and patching within weeks can be the difference between a contained incident and a major breach.

What's Inside an SBOM

At minimum, a useful SBOM contains:

- Component name and version: What library, and which exact version

- Supplier/author: Who published or maintains the component

- Dependency relationships: What depends on what (direct vs transitive)

- License information: What license each component uses

- Unique identifiers: A way to unambiguously reference each component (like Package URL or CPE)

Two standards dominate the SBOM landscape: CycloneDX and SPDX.

CycloneDX was designed specifically for application security and supply chain analysis. It's lightweight, JSON-native, and supported by OWASP. It focuses on making SBOMs actionable - not just documenting components but making it easy to link them to vulnerabilities and license obligations.

// CycloneDX format — lightweight, security-focused, OWASP-backed

{

"bomFormat": "CycloneDX",

"specVersion": "1.5",

"metadata": {

"component": {

"type": "application",

"name": "my-application",

"version": "1.0.0"

}

},

"components": [

{

"type": "library",

"name": "pandas",

"version": "2.1.0",

"purl": "pkg:pypi/pandas@2.1.0",

"licenses": [

{ "license": { "id": "BSD-3-Clause" } }

]

},

{

"type": "library",

"name": "numpy",

"version": "1.25.2",

"purl": "pkg:pypi/numpy@1.25.2",

"licenses": [

{ "license": { "id": "BSD-3-Clause" } }

]

}

]

}SPDX (Software Package Data Exchange) comes from the Linux Foundation and has a broader scope. It was originally designed for license compliance and has deep support for expressing complex licensing relationships. It's widely adopted in the open-source community and is recognized as an ISO standard (ISO/IEC 5962:2021).

// SPDX format — ISO standard (ISO/IEC 5962:2021), license-compliance focused

{

"spdxVersion": "SPDX-2.3",

"dataLicense": "CC0-1.0",

"SPDXID": "SPDXRef-DOCUMENT",

"name": "my-application",

"packages": [

{

"name": "pandas",

"SPDXID": "SPDXRef-pandas",

"versionInfo": "2.1.0",

"downloadLocation": "https://pypi.org/project/pandas/2.1.0/",

"filesAnalyzed": false,

"licenseConcluded": "BSD-3-Clause",

"licenseDeclared": "BSD-3-Clause"

},

{

"name": "numpy",

"SPDXID": "SPDXRef-numpy",

"versionInfo": "1.25.2",

"downloadLocation": "https://pypi.org/project/numpy/1.25.2/",

"filesAnalyzed": false,

"licenseConcluded": "BSD-3-Clause",

"licenseDeclared": "BSD-3-Clause"

}

]

}Which should you use? In practice, most modern tools support both. If your primary concern is security and vulnerability management, CycloneDX tends to be more ergonomic. If you're dealing with complex licensing requirements or working with the Linux Foundation ecosystem, SPDX is a natural fit. Many organizations generate both and convert between them as needed.

How SBOMs Get Generated

There are three main approaches, and most teams end up using a combination.

Source Code and Manifest Analysis

The most common approach is analyzing your project's manifest and lock files - package-lock.json, requirements.txt, go.sum, pom.xml, Gemfile.lock. Tools parse these files to build the full dependency tree without needing to execute any code.

This is fast and reliable for declared dependencies, but it misses anything that doesn't go through a package manager - vendored code, embedded libraries, or dependencies loaded at runtime.

Container Image Scanning

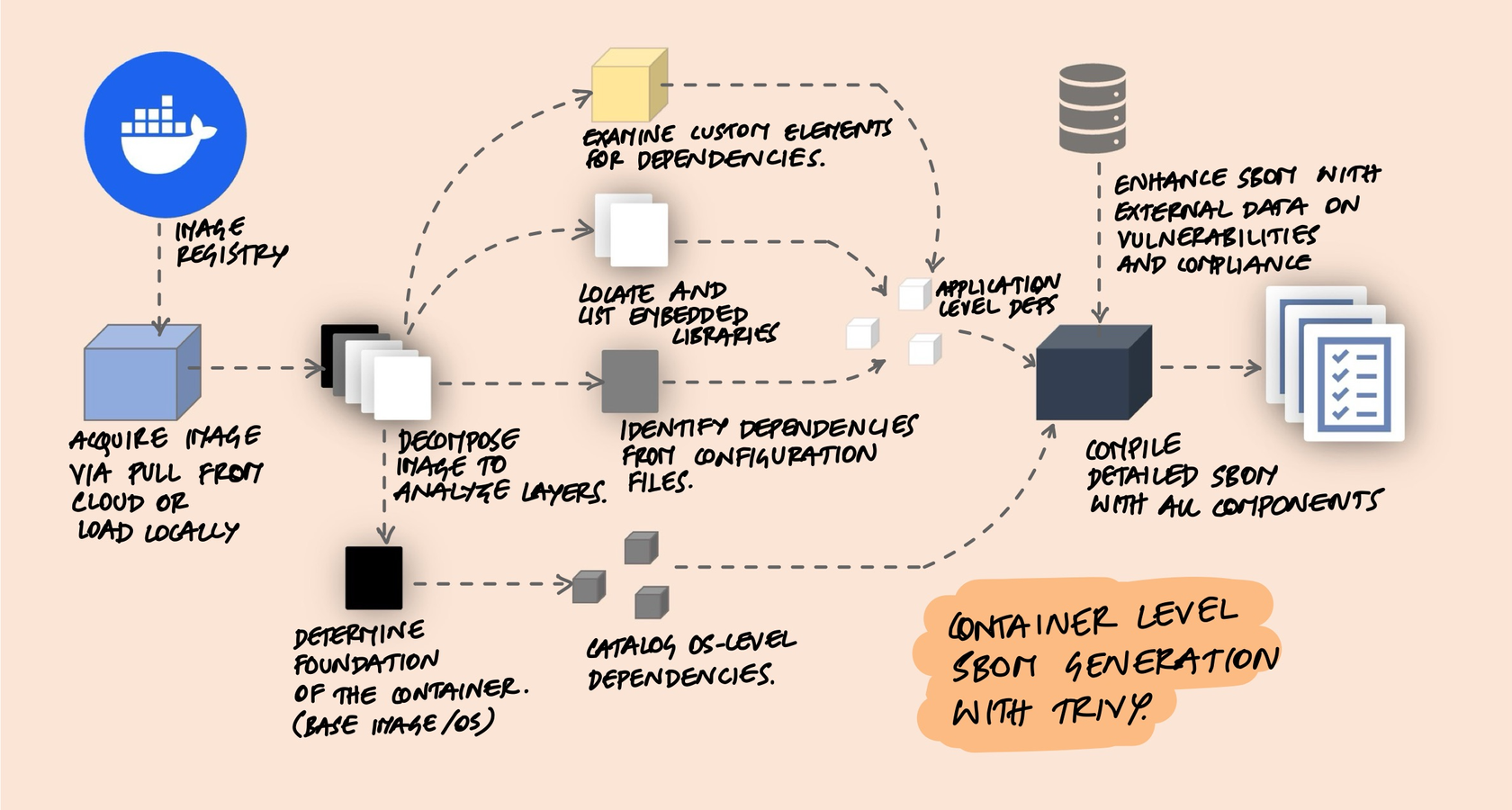

For containerized applications, tools like Trivy scan the entire container image - not just your application code but also the OS-level packages in the base image. This matters because your python:3.11 base image ships with hundreds of system packages that don't appear in any application-level manifest file.

The process involves pulling the container image, decomposing its layers, identifying the base OS, cataloging OS-level packages (via dpkg, rpm, etc.), detecting application-level dependencies from manifest files, scanning for embedded libraries, and compiling everything into a single SBOM. Tools like Syft and Trivy handle all of this automatically.

Container scanning gives you the fullest picture, but it only captures what's in the image at scan time. If your runtime configuration pulls in additional dependencies, those won't be captured.

Binary Scanning

Sometimes you don't have source code or manifest files - you have a compiled binary, a vendor-provided .jar, or a proprietary shared library. Binary scanning tools attempt to identify components by examining the binary itself. They look for embedded strings (version numbers, copyright notices, library names), file hashes that match known packages, and structural patterns like ELF headers or PE metadata.

Tools like Syft can scan binaries and attempt to extract dependency information. For Java, this works reasonably well because .jar files contain pom.properties and manifest metadata. For Go binaries, the compiler embeds module information that tools can read directly. But for C/C++ binaries, the story is different - there's no standardized way to embed dependency metadata, so tools fall back to heuristics like matching strings or file hashes against known libraries.

This makes binary scanning inherently less reliable than manifest analysis. A statically linked C library leaves almost no trace in the final binary. Vendored code that's been modified won't match any known hash. Version strings can be stripped during compilation. And even when a tool does identify a component, it may get the version wrong - reporting the version of the library that was linked rather than the patched fork actually in use. Binary scanning is useful as a last resort when source isn't available, but you should treat its output as a starting point that needs verification, not a definitive inventory.

CI/CD Integration

The most practical approach is generating SBOMs automatically as part of your build pipeline. Every build produces an SBOM alongside the artifact, so your inventory stays current without anyone needing to remember to run a scan.

A typical setup looks like: build your artifact, generate the SBOM from your manifest and lock files using a tool like CycloneDX CLI, upload the SBOM to an analysis platform like Dependency-Track, and gate the pipeline on policy violations.

The key insight is that SBOM generation should be a build step, not a separate process. If it's separate, it becomes something people skip when they're in a hurry - which is exactly when you need it most.

The Hard Parts

SBOMs solve a real problem, but the ecosystem has rough edges that are worth understanding before you invest in tooling.

Incomplete Data

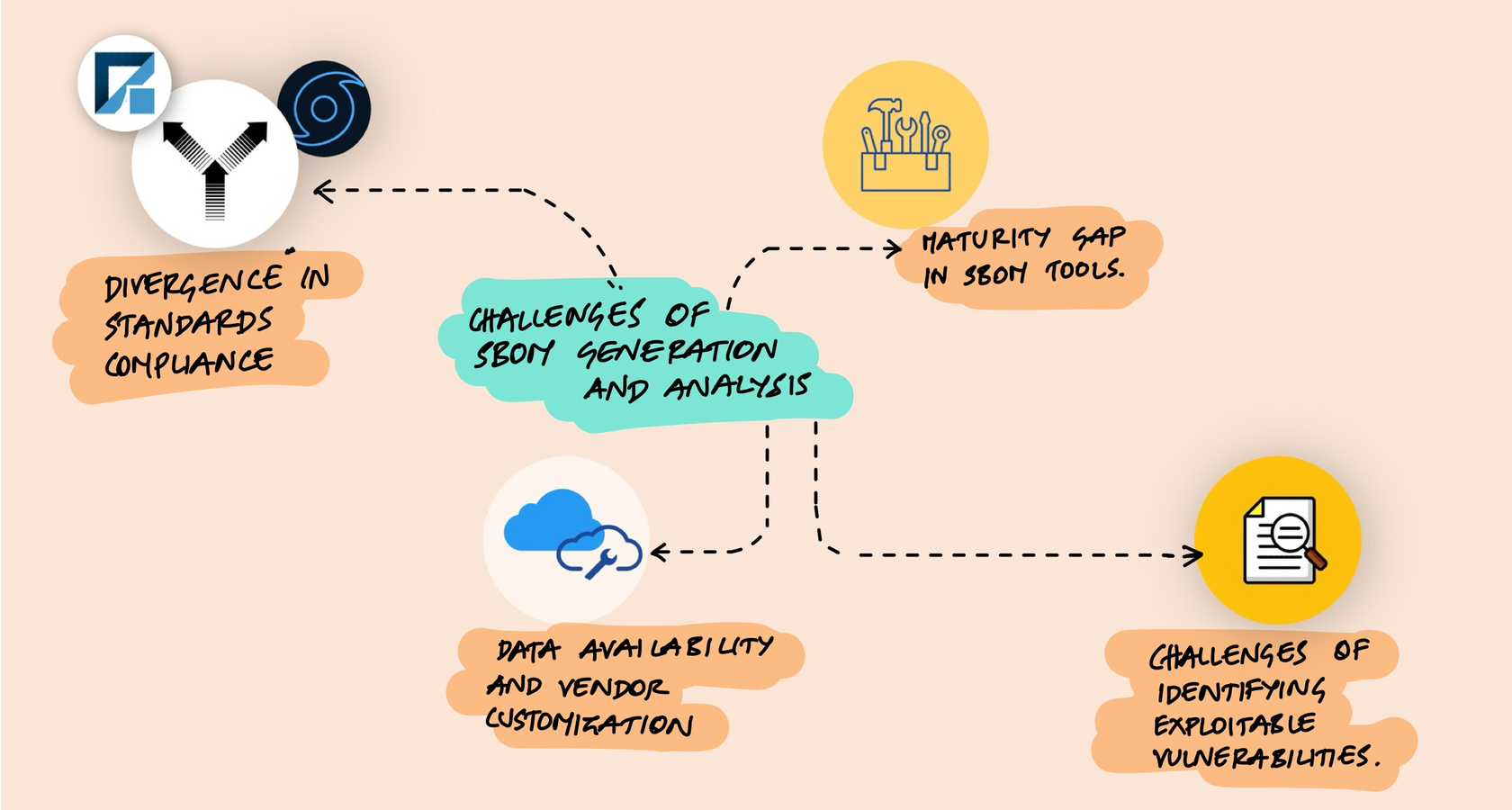

Not all software vendors provide comprehensive component information. Some omit transitive dependencies. Others use proprietary formats that don't map cleanly to SPDX or CycloneDX. The result is that an SBOM generated by one tool for the same application might look different from one generated by another tool - which undermines the whole point of having a standard format.

Tool Inconsistency

Different SBOM generators interpret standards differently. I've seen cases where two tools analyzing the same package-lock.json produce different component counts because they disagree on what constitutes a "component." Is a dev dependency a component? What about optional dependencies? Peer dependencies? The standards leave enough ambiguity that tooling diverges.

If no single tool covers your entire stack, you'll need multiple tools and a way to merge their outputs. CycloneDX CLI handles this well - it can merge SBOMs from different sources into a single document.

The Exploitability Question

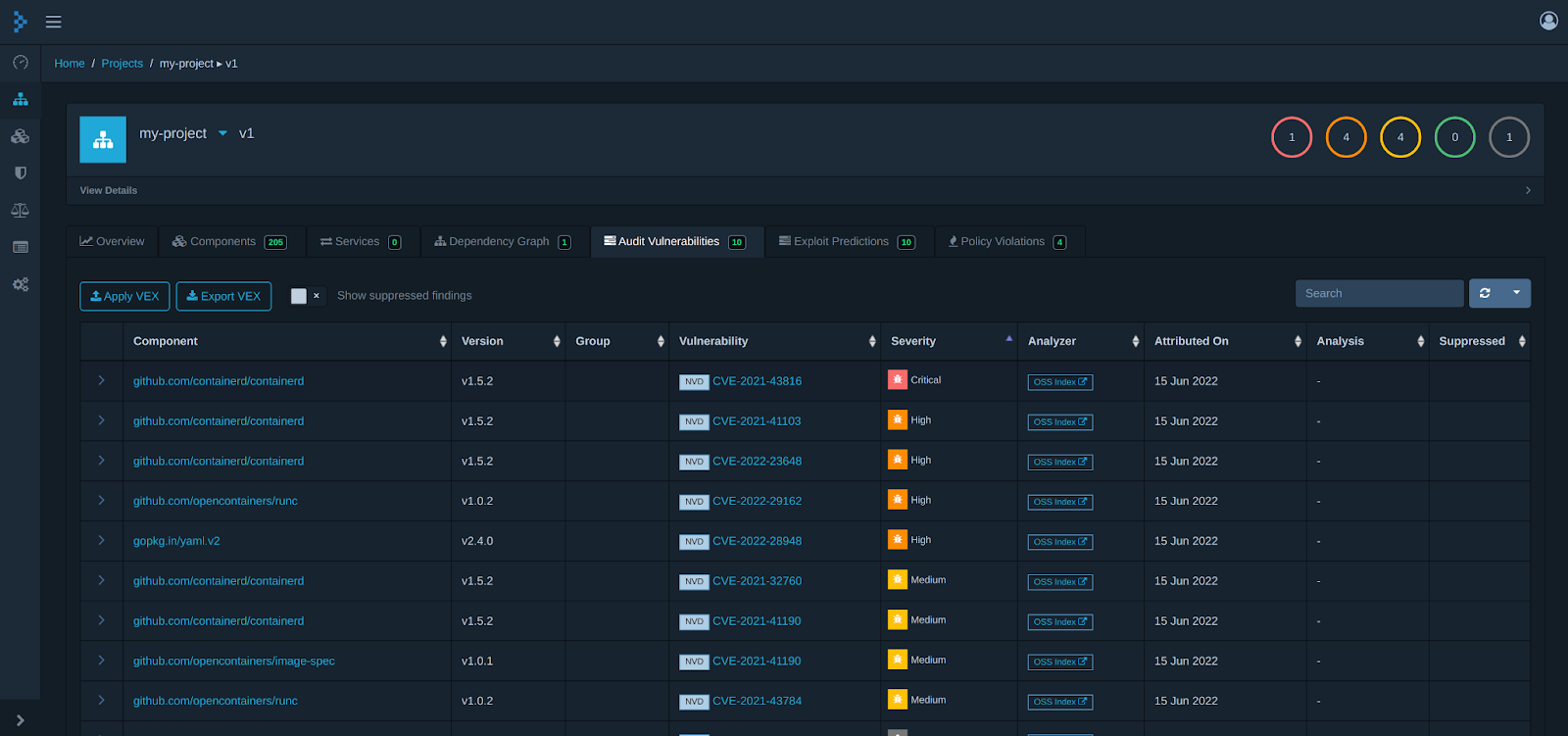

This is the biggest practical challenge. An SBOM might tell you that your application contains a component with a known CVE, but that doesn't necessarily mean your application is vulnerable. Maybe your code never calls the affected function. Maybe the vulnerability requires a specific configuration you don't use. Maybe it's in a test dependency that never reaches production.

This is where VEX (Vulnerability Exploitability eXchange) comes in. A VEX document is a companion to an SBOM that says "yes, this component has CVE-XXXX, but it's not exploitable in our context because..." VEX is the bridge between knowing what's in your software and knowing what actually puts you at risk. It's still maturing as a standard, and creating accurate VEX documents requires manual analysis - but it's the missing piece that makes SBOMs truly actionable.

An SBOM without exploitability context gives you a list of everything that could be wrong. VEX tells you what actually is. The difference matters when you're looking at hundreds of CVEs and need to decide what to fix first.

Making It Work: Tools and Prioritization

Vulnerability Databases

An SBOM tells you what's in your software. But to know if any of those components have known security issues, you need something to check them against. That's where vulnerability databases come in.

The foundation of the ecosystem is the CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) program, run by MITRE. When a new vulnerability is discovered, it gets assigned a unique identifier like CVE-2021-44228. This ID becomes the universal reference that every tool, database, and advisory uses to talk about the same issue.

NVD (National Vulnerability Database), maintained by NIST, enriches each CVE with severity scores (CVSS), affected version ranges, and references. It's the most widely used source and what most SCA tools query by default. OSS Index (by Sonatype) focuses specifically on open-source components and maps vulnerabilities to package manager coordinates - so instead of searching by library name, you can query by the exact pkg:npm/lodash@4.17.20 you found in your SBOM. GitHub Advisory Database aggregates CVEs along with community-submitted advisories and maps them directly to GitHub ecosystem packages, which is what powers Dependabot alerts.

The practical implication: when you upload an SBOM to an analysis tool, it takes each component and its version, queries these databases, and tells you which known vulnerabilities apply. The richer the SBOM (exact versions, package URLs), the more accurate the matching.

SCA Tools and Dependency-Track

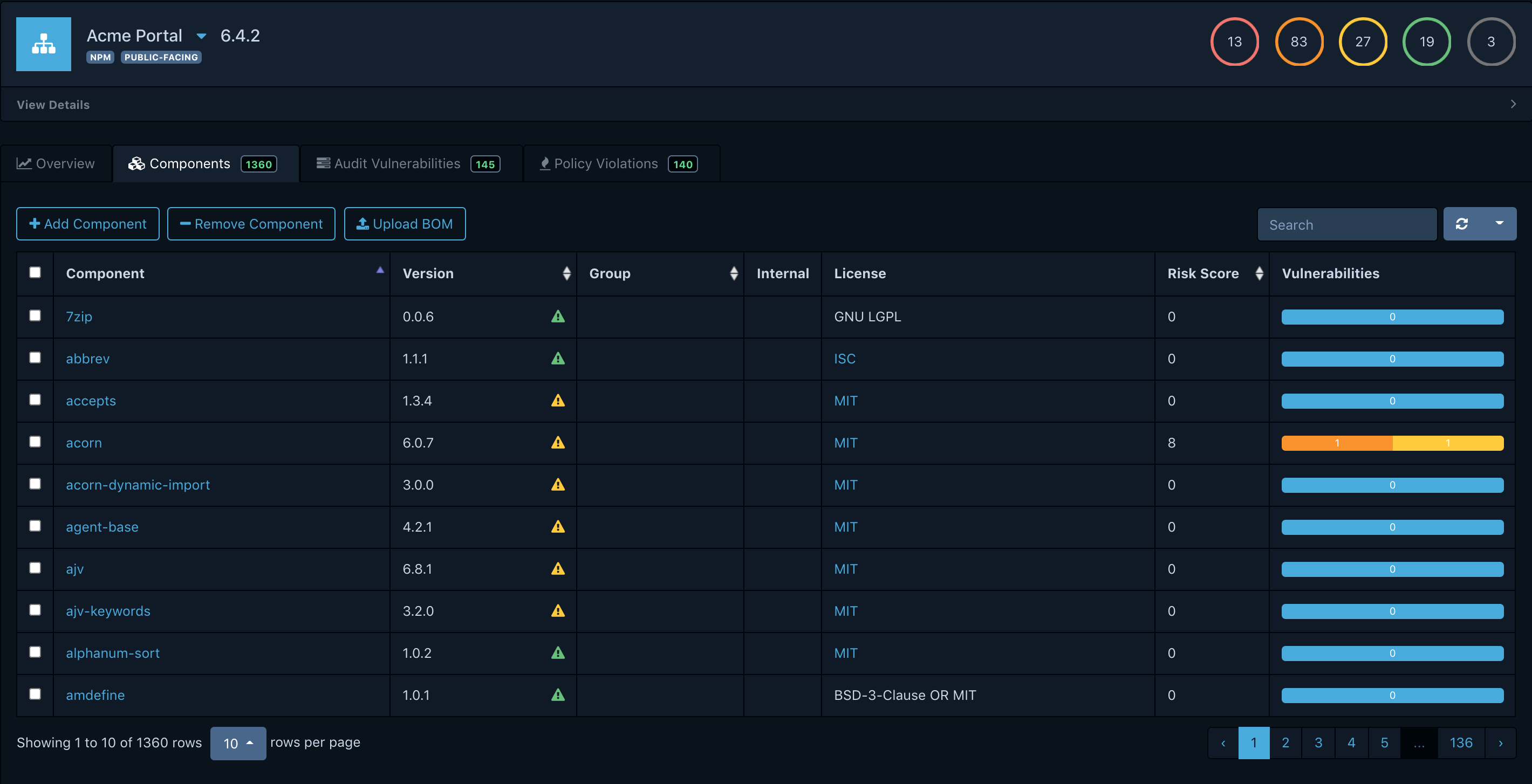

Software Composition Analysis (SCA) tools automate this entire workflow - scanning applications, generating SBOMs, and cross-referencing components against the vulnerability databases above. Snyk, GitHub's dependency graph with Dependabot, and CycloneDX CLI are all common choices for generation. For analysis, OWASP Dependency-Track is the most established open-source option.

Dependency-Track ingests SBOMs (in CycloneDX or SPDX format), cross-references them against multiple vulnerability databases (NVD, OSS Index, VulnDB), and gives you a dashboard showing what's at risk across all your projects.

What makes Dependency-Track useful in practice is its continuous monitoring. You don't just scan once - it keeps tracking your components against new vulnerability disclosures. When a new CVE drops, you get a notification for every project that contains the affected component. It also supports policy creation, so you can enforce rules like "no GPL dependencies in production services" or "no components with critical unpatched CVEs."

Prioritizing What to Fix

A typical scan might surface hundreds of CVEs across your applications. You can't fix them all at once, so you need a way to decide what matters most. Three inputs help here: CVSS, EPSS, and KEV.

CVSS (Common Vulnerability Scoring System) answers the question: how bad is this if it gets exploited? It rates severity on a 0-10 scale based on factors like attack vector (does the attacker need network access or local access?), complexity (is it trivial to exploit or does it require specific conditions?), and impact (does it compromise confidentiality, integrity, or availability?). A CVSS of 9.8 means it's remotely exploitable with no special conditions and gives the attacker full control. A CVSS of 3.1 means it requires local access and has limited impact.

EPSS (Exploit Prediction Scoring System) answers a different question: how likely is it that someone will actually exploit this? It uses machine learning on historical exploit data, vulnerability characteristics, and threat intelligence to produce a probability score between 0 and 1. An EPSS of 0.97 means there's a 97% chance this vulnerability will be exploited in the wild within the next 30 days. An EPSS of 0.01 means almost nobody is targeting it.

The insight is that CVSS and EPSS measure different things, and they don't always correlate. A vulnerability can score 9.8 on CVSS (theoretically devastating) but 0.02 on EPSS (nobody is actually exploiting it - maybe because the affected software is rare, or the exploit requires unusual conditions). Conversely, a CVSS 6.5 vulnerability with an EPSS of 0.85 is being actively targeted right now.

KEV (Known Exploited Vulnerabilities) is CISA's catalog of vulnerabilities that are confirmed to be actively exploited in the wild. Unlike EPSS which predicts likelihood, KEV is based on evidence - a vulnerability lands on the KEV list only when CISA has confirmed real-world exploitation. The catalog currently contains over 1,100 vulnerabilities and is updated regularly.

KEV matters because it removes all guesswork. If a vulnerability in your SBOM appears on the KEV list, it's not a theoretical risk - someone is already using it to break into systems. CISA's Binding Operational Directive 22-01 requires federal agencies to remediate KEV vulnerabilities within strict deadlines (typically 2-3 weeks). Even if you're not a federal agency, treating KEV entries as mandatory urgent fixes is a good baseline policy.

The practical approach: KEV items first (confirmed exploits, no debate), then high CVSS with high EPSS (severe and likely to be exploited), then high CVSS with low EPSS (severe but not actively targeted), then the rest. This prevents the common trap where teams spend weeks patching theoretically severe vulnerabilities while ignoring moderate ones that attackers are actively using.

Key Takeaway

SBOMs aren't a silver bullet for software security, but they're the foundation that makes everything else work. You can't manage vulnerabilities in components you don't know about. You can't ensure license compliance for dependencies you haven't inventoried. You can't respond quickly to incidents when you first need to figure out what's running where.

The practical path is straightforward: generate SBOMs as part of your build pipeline, feed them into an analysis tool like Dependency-Track, and set up alerts for new vulnerabilities in your components. Start with your most critical applications and expand from there. The tooling isn't perfect - you'll run into inconsistencies between generators and noise from unexploitable CVEs - but it's good enough to provide real value. And the ecosystem is improving fast.