Concurrency

Your application is slow. Users are complaining. The obvious fix is to throw more hardware at it - a bigger server, more RAM, faster CPUs. It works for a while. Then traffic doubles again, and you are back where you started, except now you are paying for a very expensive machine that still cannot keep up. The real problem is not the hardware. It is how your application uses it.

The Problem With Bigger Machines

When an application runs as a single process, there is a hard limit to how much work it can do. You can give that process more memory and faster CPUs - this is called vertical scaling - but you will hit a ceiling. At some point, you cannot buy a bigger machine. Or the cost becomes absurd.

There is another problem. A single process is a single point of failure. If it crashes, everything goes down. If you need to deploy a new version, you have to restart it, which means downtime.

The twelve-factor app approach to this is simple: instead of making one process do more work, run more processes. This is horizontal scaling, and it changes how you think about your application.

What Concurrency Means Here

Concurrency in the twelve-factor context is not about threads or async/await. It is about the process model - the idea that your application should be designed as a set of independent processes, each doing a specific type of work.

Think of it this way. A restaurant does not handle more customers by making one waiter work faster. It hires more waiters. And it does not ask waiters to also cook food. It has separate roles - waiters handle customers, cooks handle food, a dishwasher handles dishes. Each role can be scaled independently based on demand.

Your application should work the same way.

Process Types

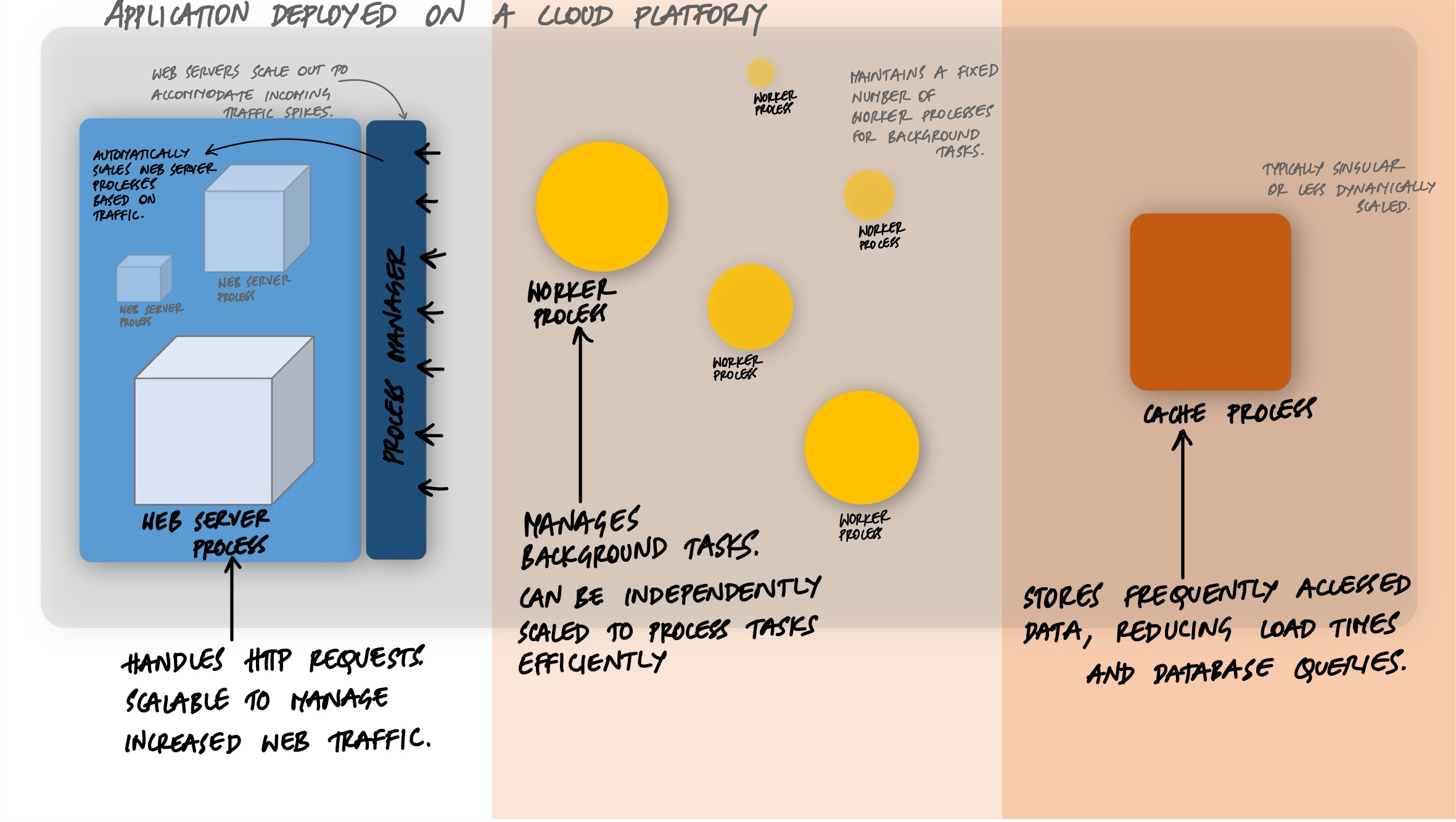

A typical web application has different kinds of work to do. HTTP requests need to be served. Background jobs need to be processed. Scheduled tasks need to run at specific times. Each of these is a different process type.

A Procfile makes this explicit. It is a simple file that declares each process type and the command to run it:

web: gunicorn app:application --workers 4 --bind 0.0.0.0:$PORT

worker: celery -A tasks worker --concurrency 4

clock: celery -A tasks beat --schedule /tmp/celerybeat-scheduleThree process types. The web process handles HTTP requests. The worker process handles background jobs. The clock process triggers scheduled tasks. Each runs independently. Each can be scaled independently.

Scaling Web Processes

Let's start with the most common process type. A web process receives HTTP requests and returns responses. When you run a Python web application with Gunicorn, you are already using the process model:

# Run 4 worker processes, each handling requests independently

gunicorn app:application --workers 4 --bind 0.0.0.0:8000Gunicorn starts a master process that manages four worker processes. Each worker is a separate OS process with its own memory space. When a request comes in, Gunicorn routes it to an available worker. If one worker is busy handling a slow database query, the other three can still serve requests.

This is process-based concurrency in action. You did not write any threading code. You did not use async/await. You just told Gunicorn to run four processes, and now your application can handle four requests at the same time.

Need to handle more traffic? Increase the worker count:

# More traffic? More workers.

gunicorn app:application --workers 8 --bind 0.0.0.0:8000A common rule of thumb is (2 * CPU cores) + 1 workers per machine. On a 4-core server, that is 9 workers. But you are still limited by the machine. The real power comes when you run the same process on multiple machines.

Scaling Worker Processes

Web processes handle the fast, synchronous work - receive a request, query the database, return a response. But what about work that takes minutes or hours? Sending emails, processing images, generating reports, running ML inference.

This is where worker processes come in. Instead of making the web process do everything (and making users wait), you push slow work onto a queue and let workers pick it up:

# tasks.py

from celery import Celery

app = Celery("tasks", broker="redis://localhost:6379/0")

@app.task

def generate_report(user_id, report_type):

# This takes 30 seconds. You do not want a web

# process tied up doing this.

data = fetch_data(user_id, report_type)

pdf = render_pdf(data)

upload_to_s3(pdf)

send_email(user_id, pdf_url=pdf.url)And in the web process, you just queue the task:

# Inside a Flask/Django view

from tasks import generate_report

@app.route("/reports", methods=["POST"])

def request_report():

generate_report.delay(current_user.id, request.form["type"])

return jsonify({"status": "processing"}), 202The web process responds immediately. The report generation happens in a completely separate worker process. The user does not wait 30 seconds for a response.

Here is the important part: you scale web and worker processes independently. If your application gets a spike in report requests but web traffic stays the same, you only need more workers:

# Normal day: 4 workers

celery -A tasks worker --concurrency 4

# Month-end reporting spike: 16 workers

celery -A tasks worker --concurrency 16You did not touch the web processes at all. Each process type scales based on its own demand.

Clock Processes

The third common process type is the clock (or scheduler). It does not do the actual work - it just tells workers when to start tasks:

# celeryconfig.py

from celery.schedules import crontab

beat_schedule = {

"daily-cleanup": {

"task": "tasks.cleanup_expired_sessions",

"schedule": crontab(hour=3, minute=0),

},

"send-weekly-digest": {

"task": "tasks.send_weekly_digest",

"schedule": crontab(hour=9, minute=0, day_of_week=1),

},

}You only ever run one clock process. It just publishes tasks to the queue. Workers pick them up and do the actual work. This separation matters because if you accidentally ran two clock processes, every scheduled task would run twice.

Horizontal Scaling With Docker Compose

On a single machine, you can scale process types using Docker Compose:

# docker-compose.yml

services:

web:

build: .

command: gunicorn app:application --workers 4 --bind 0.0.0.0:8000

ports:

- "8000:8000"

environment:

- DATABASE_URL=postgres://db:5432/app

- REDIS_URL=redis://redis:6379/0

worker:

build: .

command: celery -A tasks worker --concurrency 4

environment:

- DATABASE_URL=postgres://db:5432/app

- REDIS_URL=redis://redis:6379/0

clock:

build: .

command: celery -A tasks beat --schedule /tmp/celerybeat-schedule

environment:

- REDIS_URL=redis://redis:6379/0

redis:

image: redis:7-alpine

db:

image: postgres:16-alpineSame codebase, same Docker image, different commands. The only difference between web and worker is the command that starts them. Need more workers?

docker compose up --scale worker=3Now you have three worker containers, each running 4 Celery workers, for a total of 12 concurrent background task processors. The web and clock processes are untouched.

Horizontal Scaling With Kubernetes

In production, Kubernetes takes this further. Each process type becomes a Deployment that can be scaled independently:

# web-deployment.yaml

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: web

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: myapp

process: web

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: myapp

process: web

spec:

containers:

- name: web

image: myapp:latest

command: ["gunicorn", "app:application", "--workers", "4"]

resources:

requests:

cpu: "500m"

memory: "256Mi"# worker-deployment.yaml

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: worker

spec:

replicas: 5

selector:

matchLabels:

app: myapp

process: worker

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: myapp

process: worker

spec:

containers:

- name: worker

image: myapp:latest

command: ["celery", "-A", "tasks", "worker", "--concurrency", "4"]

resources:

requests:

cpu: "1000m"

memory: "512Mi"Notice the resource requests are different. Web processes need less CPU and memory because they mostly wait on I/O. Worker processes need more because they do heavy computation. You allocate resources based on what each process type actually needs.

Kubernetes can also scale automatically based on load:

# Scale web pods when CPU exceeds 70%

kubectl autoscale deployment web --min=2 --max=10 --cpu-percent=70

# Scale workers independently

kubectl autoscale deployment worker --min=3 --max=20 --cpu-percent=70Web processes scale from 2 to 10 based on HTTP traffic. Worker processes scale from 3 to 20 based on queue depth. Each process type responds to its own demand.

Why Not Threads?

A common question: why run multiple processes instead of using threads within one process?

Threads share memory, which makes them faster for some operations but introduces a whole class of bugs - race conditions, deadlocks, and memory corruption. Processes are isolated. If one process crashes, the others keep running. If one process has a memory leak, you can restart it without affecting the rest.

That said, processes and threads are not mutually exclusive. Gunicorn workers can use threads internally. Celery workers can use a thread pool. The twelve-factor principle is about how you scale your application as a whole - by running more processes - not about what happens inside each process.

The distinction matters at the architecture level. When your team asks “how do we handle more traffic?”, the answer should be “add more web processes”, not “rewrite the application to be multithreaded”.

Process Management

One important rule: your application should not manage its own processes. It should not daemonize itself, write PID files, or restart crashed workers. That is the job of the platform.

In development, a tool like honcho (Python's Foreman equivalent) reads your Procfile and manages all process types:

# Install honcho

pip install honcho

# Start all processes defined in Procfile

honcho start

# Output:

# 14:30:01 web.1 | [INFO] Listening at: http://0.0.0.0:8000

# 14:30:01 worker.1 | [INFO] celery@host ready.

# 14:30:01 clock.1 | [INFO] beat: Starting...In production, the platform handles this. Docker restarts crashed containers. Kubernetes maintains the desired replica count. If a worker dies, Kubernetes starts a new one automatically. Your application just needs to start, do its job, and shut down cleanly.

The Key Insight

The core idea behind the concurrency principle is this: your application is not one process. It is a formation of processes, each with a specific role, each independently scalable.

This changes how you think about performance problems. Instead of asking “how do I make this one thing faster?”, you ask “which process type is the bottleneck, and how many more do I need?”

Web processes too slow? Add more web processes. Background queue backing up? Add more workers. The application code does not change. The architecture handles the load because it was designed to scale horizontally from the beginning.