Understanding Backing Services

A few years ago, our team had to migrate a production database from a self-serviced PostgreSQL instance to a managed PostgreSQL service. The migration itself took careful planning - data transfer, replication, cutover timing. But the application change? One environment variable. We updated the connection string, redeployed, and the app connected to its new database without a single code change. That wasn't luck. It was the result of treating the database as what the 12-factor methodology calls a backing service - an attached resource that the application connects to through configuration, not code.

What Is a Backing Service?

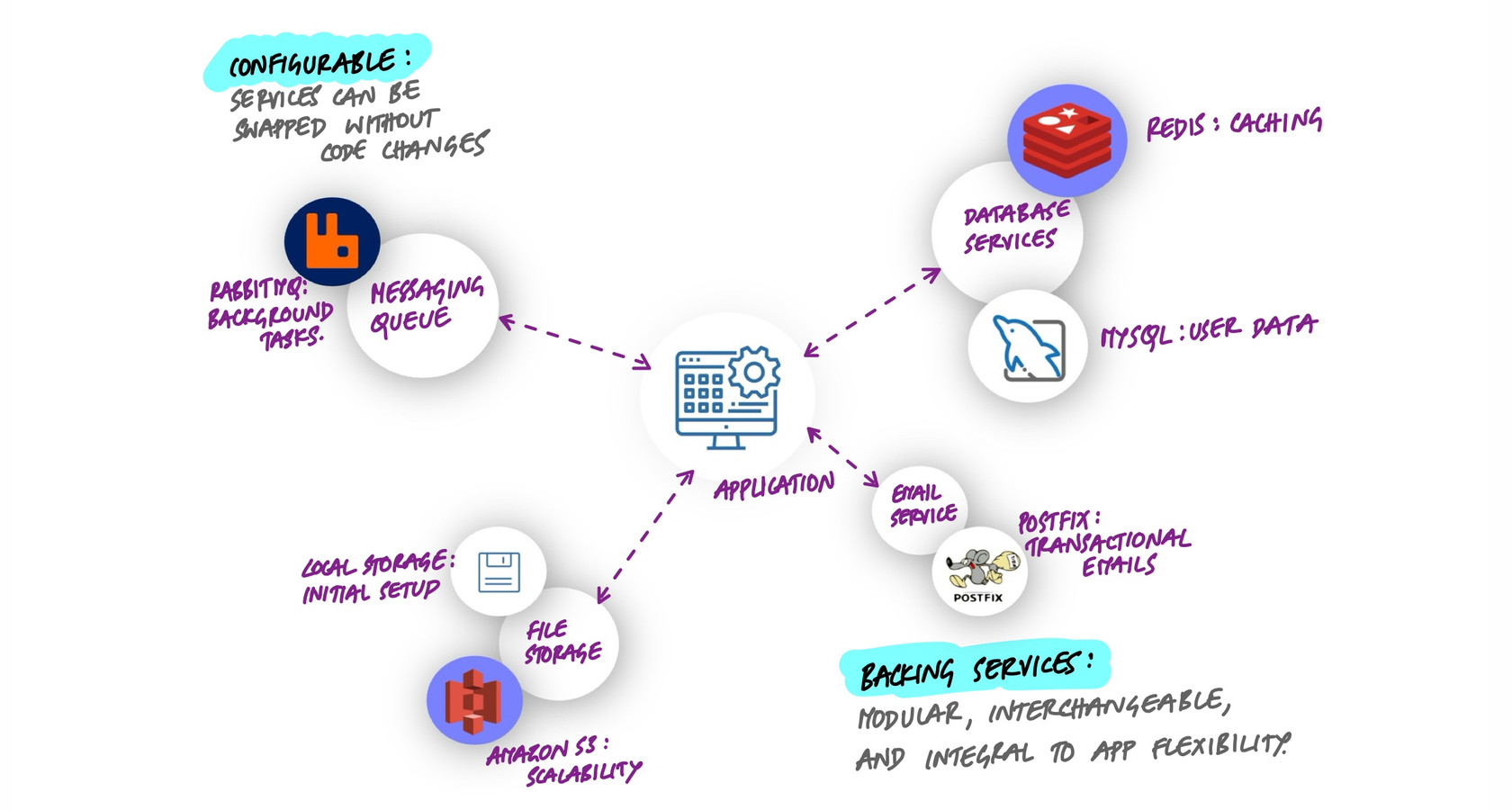

A backing service is any service your application consumes over the network as part of its normal operation. Databases, caches, message queues, email providers, object storage, monitoring systems, API gateways - all backing services. The defining characteristic is that your application depends on them but doesn't own them. They could be running on the same machine, in a different availability zone, or on the other side of the world. Your application shouldn't know or care.

The 12-factor app methodology captures this idea with a simple principle: treat backing services as attached resources. An attached resource can be connected and disconnected through configuration alone, the same way you might unplug a USB drive from one port and plug it into another.

The practical list is longer than most people think:

- Datastores: PostgreSQL, MySQL, MongoDB, DynamoDB

- Caches: Redis, Memcached, Varnish

- Message brokers: RabbitMQ, Kafka, Amazon SQS

- Email delivery: SendGrid, Amazon SES, Postmark

- Object storage: Amazon S3, Google Cloud Storage, MinIO

- Search engines: Elasticsearch, Algolia, Meilisearch

- Monitoring: Datadog, Prometheus, New Relic

- Third-party APIs: Stripe, Twilio, Auth0

Every one of these should be swappable without touching application code. That's the standard to aim for.

The Connection String Is the Entire Relationship

Here's the insight that makes this pattern click: the connection string encodes everything your application needs to know about a backing service. Protocol, credentials, host, port, resource path - the complete relationship is in that one string.

# Each backing service is a URL in your environment

DATABASE_URL=postgresql://app_user:secret@db.internal:5432/myapp

REDIS_URL=redis://:token@cache.internal:6379/0

AMQP_URL=amqp://guest:guest@queue.internal:5672/

S3_ENDPOINT=https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

SMTP_URL=smtp://apikey:SG.xxx@smtp.sendgrid.net:587

SEARCH_URL=https://admin:key@search.internal:9200Look at what this buys you. Switching from a local PostgreSQL to Amazon RDS? Change the host in DATABASE_URL. Moving from self-hosted Redis to ElastiCache? Update REDIS_URL. Migrating email from SendGrid to Amazon SES? New SMTP_URL. In every case, the application code stays exactly the same.

This works because the connection string is an abstraction boundary. Everything above it (your application code) doesn't care about what's below it (the specific service implementation). The same code that talks to a local PostgreSQL in development talks to a managed cluster with read replicas in production. The URL changes; the code doesn't.

The Attachment Test

Here's a quick way to evaluate whether your application truly treats its dependencies as backing services. Ask this question for each external dependency:

Can I swap this service for a different provider by changing only configuration - no code changes, no redeployment of application logic?

If the answer is yes, you have a properly attached resource. If not, you have a coupling problem. Common coupling leaks include:

- Hardcoded connection details. A database host embedded in application code instead of read from an environment variable.

- Provider-specific SDKs with no abstraction. Directly calling

s3.putObject()in your business logic instead of going through a storage interface. When you want to switch to Google Cloud Storage, you're rewriting every file operation. - Implicit local assumptions. Code that assumes the file system is shared between instances, or that a service is always reachable with zero latency.

- Configuration spread across code. Database credentials in a config file checked into the repo, API keys in constants, queue names in hardcoded strings.

The fix in every case is the same: push the binding details into environment configuration and access the service through an abstraction.

Writing Code That Doesn't Care

Connection strings handle the "where" - which host, which credentials, which protocol. But you also need your code to not care about the "what" - which specific implementation is behind the interface. This is where abstraction layers earn their keep.

Consider file storage. Your application needs to store and retrieve files. It shouldn't matter whether those files live on a local disk, in Amazon S3, or in Google Cloud Storage. The pattern looks like this:

# Your application code calls this interface

class FileStorage(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def save(self, key: str, data: bytes) -> str: ...

@abstractmethod

def get(self, key: str) -> bytes: ...

@abstractmethod

def delete(self, key: str) -> None: ...

# In development: local file system

class LocalStorage(FileStorage): ...

# In production: Amazon S3

class S3Storage(FileStorage): ...

# The app doesn't know or care which one it's using

storage = create_storage(os.environ["STORAGE_BACKEND"])

storage.save("uploads/avatar.png", image_bytes)The same pattern applies to every backing service. Email sending goes through a mailer interface. Caching goes through a cache interface. Queue publishing goes through a message broker interface. Each interface has concrete implementations that can be swapped via configuration.

This isn't over-engineering. It's the minimum abstraction needed to make your application portable. Without it, every infrastructure decision becomes a code decision, and every migration becomes a rewrite.

What Happens When Services Go Down

Here's where the real maturity of your backing service architecture shows. Connecting to services is easy. Handling their failure gracefully is hard. And every backing service will fail at some point - databases go unreachable, cache servers restart, third-party APIs return 503s.

The question is: what does your application do when that happens?

Timeouts

Every call to a backing service needs a timeout. Without one, a slow or unresponsive service can hold your application threads hostage indefinitely. A database query that normally takes 50ms but hangs for 30 seconds during a network partition will cascade into request queues backing up, thread pools exhausting, and eventually your entire application becoming unresponsive - all because one backing service had a bad moment.

Set explicit timeouts for every external call. Connection timeout (how long to wait for the TCP handshake), read timeout (how long to wait for a response), and overall request timeout (the total budget for the operation).

Retries with Backoff

Transient failures are normal. A network blip, a brief database failover, a momentary spike in a third-party API's latency - these resolve themselves quickly. A retry strategy with exponential backoff handles these gracefully: wait 100ms, then 200ms, then 400ms, with some jitter to prevent thundering herds.

But be careful. Not every failure is transient. Retrying a request that failed because of invalid credentials will never succeed. Retrying a write operation that partially completed can cause duplicates. Retries need to be idempotent-safe and should have a maximum count.

Circuit Breakers

When a backing service is truly down - not just slow, but consistently failing - continuing to send requests is wasteful and potentially harmful. A circuit breaker tracks the failure rate for a service. When failures exceed a threshold, the circuit "opens" and subsequent calls fail immediately without even attempting the request. After a cooldown period, the circuit "half-opens" and allows a test request through. If it succeeds, the circuit closes and normal traffic resumes.

This protects both your application (no wasted time on guaranteed failures) and the struggling service (no additional load while it's trying to recover). Libraries like pybreaker and tenacity (Python), Hystrix (Java), and Polly (.NET) implement this pattern.

Graceful Degradation

The ultimate question: if a backing service is completely unavailable, can your application still provide value? The answer should be yes, at least partially.

- Cache is down? Serve directly from the database. Slower, but functional.

- Search service is down? Fall back to basic database queries. Worse results, but users can still find things.

- Email service is down? Queue the emails locally and send them when the service recovers.

- Payment API is down? Show the user a clear message and let them retry, rather than failing silently or showing a generic error page.

Not every degradation path needs to be automatic. Sometimes the right answer is a clear error message that tells the user exactly what's happening and when to try again. What matters is that one backing service failure doesn't bring down your entire application.

Health Checks: Know Before Your Users Do

If your application runs in Kubernetes or behind a load balancer, it probably exposes health check endpoints. The common ones are:

- Liveness probe: "Is the process alive?" Returns 200 if the application hasn't crashed. This should be lightweight and should not check backing services - you don't want Kubernetes restarting your pod because a database is temporarily unreachable.

- Readiness probe: "Can this instance serve traffic?" This is where you check backing services. If the database is unreachable, the readiness probe fails, the pod is removed from the service endpoints, and traffic routes to healthy pods instead.

# Liveness: is the process healthy?

@app.route("/healthz")

def liveness():

return jsonify({"status": "ok"}), 200

# Readiness: can we serve traffic?

@app.route("/readyz")

def readiness():

checks = {

"database": check_database(),

"cache": check_redis(),

"queue": check_rabbitmq(),

}

healthy = all(checks.values())

return jsonify(checks), 200 if healthy else 503The distinction between liveness and readiness is subtle but critical. Getting it wrong - checking backing services in your liveness probe - means a database outage triggers a cascade of pod restarts across your cluster, making a bad situation much worse.

Per-Environment Configuration

The backing service pattern shines brightest when you run the same application across multiple environments. In development, you might use local services for fast iteration:

# Development

DATABASE_URL=postgresql://dev:dev@localhost:5432/myapp_dev

REDIS_URL=redis://localhost:6379/0

STORAGE_BACKEND=local

MAIL_BACKEND=console # just prints emails to stdoutIn production, every service points to managed, replicated infrastructure:

# Production

DATABASE_URL=postgresql://app:secret@primary.db.internal:5432/myapp

REDIS_URL=redis://cache.internal:6379/0

STORAGE_BACKEND=s3

S3_BUCKET=myapp-uploads-prod

MAIL_BACKEND=sendgrid

SENDGRID_API_KEY=SG.xxxSame application, same Docker image, same code. The only difference is which backing services are attached. This is what makes true build-once-deploy-anywhere possible. You build one artifact and promote it through environments by changing only the configuration that tells it which services to connect to.

Key Takeaway

The backing services principle is fundamentally about boundaries. Your application code stays on one side; the specific service implementations stay on the other. The connection string is the bridge between them, and it lives in configuration, not in code. Get this boundary right and you get portability (same app runs anywhere), flexibility (swap providers without rewrites), resilience (handle failures without cascading), and testability (mock services in tests with local implementations). Get it wrong and every infrastructure change becomes a code change, every outage becomes a total failure, and every environment is a special snowflake.