Disposability in Software Development

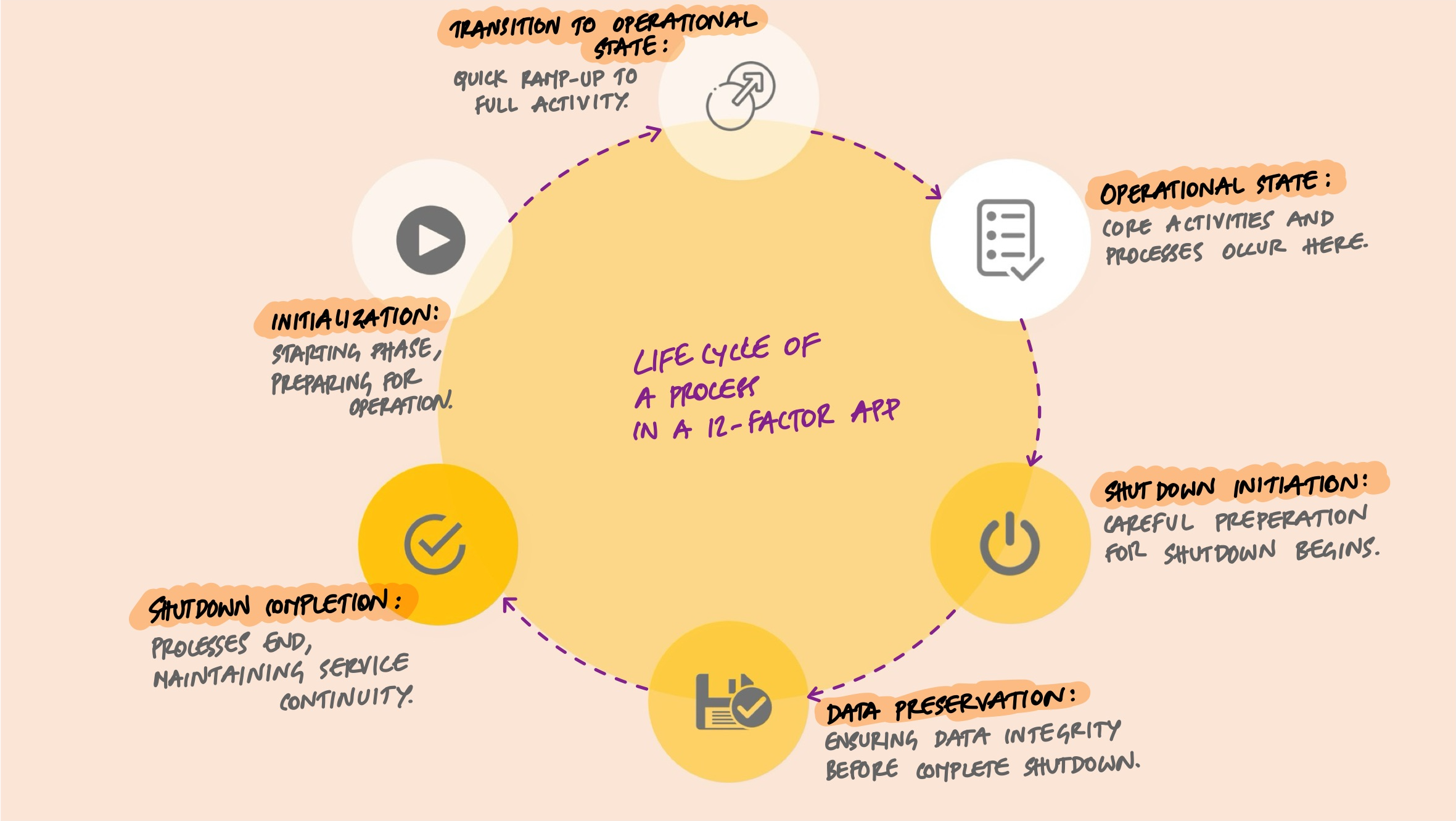

Processes get killed all the time. Deploys replace old instances with new ones. Autoscalers remove capacity when traffic drops. Containers get evicted when a node runs low on memory. Hardware fails without warning. If a process cannot start quickly and shut down cleanly, every one of these routine events becomes a potential outage - dropped requests, lost jobs, corrupted data. The 12-factor methodology says processes should be disposable: fast to start, graceful to stop, and safe to crash.

What Disposability Means

A disposable process can be started or stopped at any moment without causing harm. It does not depend on being long-lived. It does not hold critical state that would be lost if it died. It treats itself as expendable - one of potentially many identical instances that can be replaced without anyone noticing.

This matters for three reasons:

- Fast deploys. When you deploy a new version, old processes are stopped and new ones start. If startup takes thirty seconds, every deploy has thirty seconds of reduced capacity.

- Elastic scaling. When traffic spikes, new instances need to start handling requests immediately. When traffic drops, instances need to shut down without dropping in-flight work.

- Failure recovery. When a process crashes or a machine dies, the system replaces it. Fast startup means fast recovery.

Fast Startup

A process should go from launch to ready in seconds, not minutes. The faster it starts, the faster you can deploy, scale, and recover from failures.

What slows startup down:

- Loading large datasets or caches into memory before accepting requests.

- Connecting to every external service synchronously during initialization.

- Running database migrations as part of the startup sequence.

- Pre-computing derived data that could be computed lazily.

The fix is to do the minimum work needed to start accepting requests. Connections can be established lazily on first use. Caches can warm up in the background. Migrations should run as a separate admin process, not as part of startup:

from flask import Flask

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

import os

app = Flask(__name__)

# Lazy connection - engine is created at import time

# but the actual database connection happens on first query

engine = create_engine(

os.environ["DATABASE_URL"],

pool_pre_ping=True, # verify connections are alive

pool_size=5, # limit connection pool

)

@app.route("/")

def index():

# Connection is established here, on first actual use

with engine.connect() as conn:

result = conn.execute("SELECT 1")

return {"status": "healthy"}The application starts instantly. The database connection is only established when the first request needs it. If the database is temporarily unavailable at startup, the application still starts - it will fail on the first request that needs the database, not on startup itself.

Graceful Shutdown: Web Processes

When a process receives a SIGTERM signal, it should stop accepting new requests, finish any requests it is currently handling, and then exit. This is called graceful shutdown.

For a web process behind a load balancer, the sequence looks like this:

- The platform sends

SIGTERMto the process. - The load balancer stops routing new requests to this instance.

- The process finishes all in-flight requests (connection draining).

- The process closes its listening socket and exits.

Gunicorn, the production WSGI server commonly used with Flask and Django, handles this automatically. When it receives SIGTERM, it stops accepting new connections and waits for active workers to finish:

# Gunicorn handles graceful shutdown by default

# --graceful-timeout controls how long workers have to finish

gunicorn --bind 0.0.0.0:5000 \

--workers 4 \

--graceful-timeout 30 \

app:app

# On SIGTERM:

# 1. Stop accepting new connections

# 2. Wait up to 30 seconds for workers to finish

# 3. Kill workers that haven't finished

# 4. ExitFrom the user's perspective, nothing happens. Requests that were in progress complete normally. New requests go to other instances. The transition is invisible.

Graceful Shutdown: Worker Processes

Worker processes that pull jobs from a queue need a different shutdown strategy. When a worker receives SIGTERM, it should finish the current job and then stop pulling new ones.

The key pattern is delayed acknowledgment. The worker does not tell the queue "I am done with this job" until the job is actually complete. If the worker dies before finishing, the job stays in the queue and another worker picks it up:

import signal

import time

running = True

def handle_sigterm(signum, frame):

global running

print("SIGTERM received, finishing current job...")

running = False

signal.signal(signal.SIGTERM, handle_sigterm)

def process_job(job):

# Do the actual work

print(f"Processing job {job.id}")

time.sleep(2) # simulate work

while running:

job = queue.get() # pull a job from the queue

process_job(job) # do the work

queue.acknowledge(job) # THEN tell the queue it's done

print("Worker shut down cleanly")When SIGTERM arrives, the running flag is set to False. The current job finishes, gets acknowledged, and the loop exits. No jobs are lost. If the worker is killed before acknowledging, the queue treats the job as unfinished and hands it to another worker.

Celery, the most common Python task queue, supports this with the acks_late setting:

# celery_app.py

from celery import Celery

app = Celery("tasks", broker="redis://localhost:6379/0")

# Acknowledge jobs AFTER they complete, not before

app.conf.task_acks_late = True

# Reject jobs back to the queue if the worker is killed

app.conf.task_reject_on_worker_lost = True

@app.task

def send_email(user_id, template):

user = get_user(user_id)

deliver_email(user.email, template)

# Job is acknowledged only after this function returnsWith acks_late=True, if the worker dies mid-task, the job goes back to the queue. Another worker picks it up. No emails are silently lost.

What Happens Without Graceful Shutdown

When processes are killed abruptly without graceful shutdown:

- Web requests get dropped. Users see connection reset errors or 502 responses. If the request was a payment submission, the user does not know if it went through.

- Background jobs disappear. If a worker acknowledges a job before processing it (the default in many systems), and then dies, the job is gone. The email never sends. The report never generates.

- Data gets corrupted. A process writing to a file or database gets killed mid-write. The data is in an inconsistent state.

- Connections leak. Database connections and file handles that were never properly closed pile up. The database eventually runs out of connection slots.

Designing for Crash Safety

Graceful shutdown handles the expected case - the platform sends SIGTERM and gives the process time to finish. But processes also die unexpectedly. The machine loses power. The kernel kills the process with SIGKILL (which cannot be caught). The process itself hits an unhandled exception and crashes.

Designing for crash safety means assuming your process can die at any point without warning:

- Use database transactions. If a multi-step operation is wrapped in a transaction, a crash rolls back the incomplete work. The data stays consistent.

- Make jobs idempotent. If a job can be safely run twice, it does not matter if it gets retried after a crash. Use unique constraints or check-before-write patterns to prevent duplicates.

- Do not store critical state in the process. If the only copy of something important is in the process's memory, it is gone when the process dies. State belongs in a database or external store.

# Idempotent job - safe to retry after a crash

@app.task

def charge_order(order_id):

order = Order.objects.get(id=order_id)

# Check if already charged - prevents double charging on retry

if order.payment_status == "charged":

return

result = payment_gateway.charge(

amount=order.total,

idempotency_key=f"order-{order_id}",

)

order.payment_status = "charged"

order.payment_id = result.id

order.save()If the worker crashes after charging but before saving the status, the job retries. The idempotency_key tells the payment gateway not to charge again. The check at the top prevents the code from even attempting a duplicate. The operation is safe to retry any number of times.

Disposability in Containers

Kubernetes manages the process lifecycle through signals and timeouts. When a pod is being terminated:

- Kubernetes sends

SIGTERMto the process. - The process has

terminationGracePeriodSeconds(default 30 seconds) to shut down. - If the process has not exited by then, Kubernetes sends

SIGKILL.

# Kubernetes deployment (excerpt)

spec:

terminationGracePeriodSeconds: 60 # give workers time to finish

containers:

- name: worker

image: myapp:v2.3.1

lifecycle:

preStop:

exec:

command: ["sh", "-c", "sleep 5"] # wait for load balancer to drainThe preStop hook adds a small delay before SIGTERM is sent. This gives the load balancer time to stop routing traffic to this pod. Without it, the pod might receive new requests after it has started shutting down.

The terminationGracePeriodSeconds should match your longest expected job. If background jobs can take up to 60 seconds, set the grace period to at least 60 seconds so workers have time to finish.

Key Takeaway

Disposable processes start fast and stop clean. Fast startup means seconds, not minutes - defer heavy initialization, connect lazily, run migrations separately. Graceful shutdown means handling SIGTERM, finishing in-flight work, and exiting without dropping requests or losing jobs. Beyond graceful shutdown, design for crashes too - use transactions, make jobs idempotent, and keep critical state in external stores. When processes are truly disposable, deploys become routine, scaling becomes automatic, and failures become recoverable.