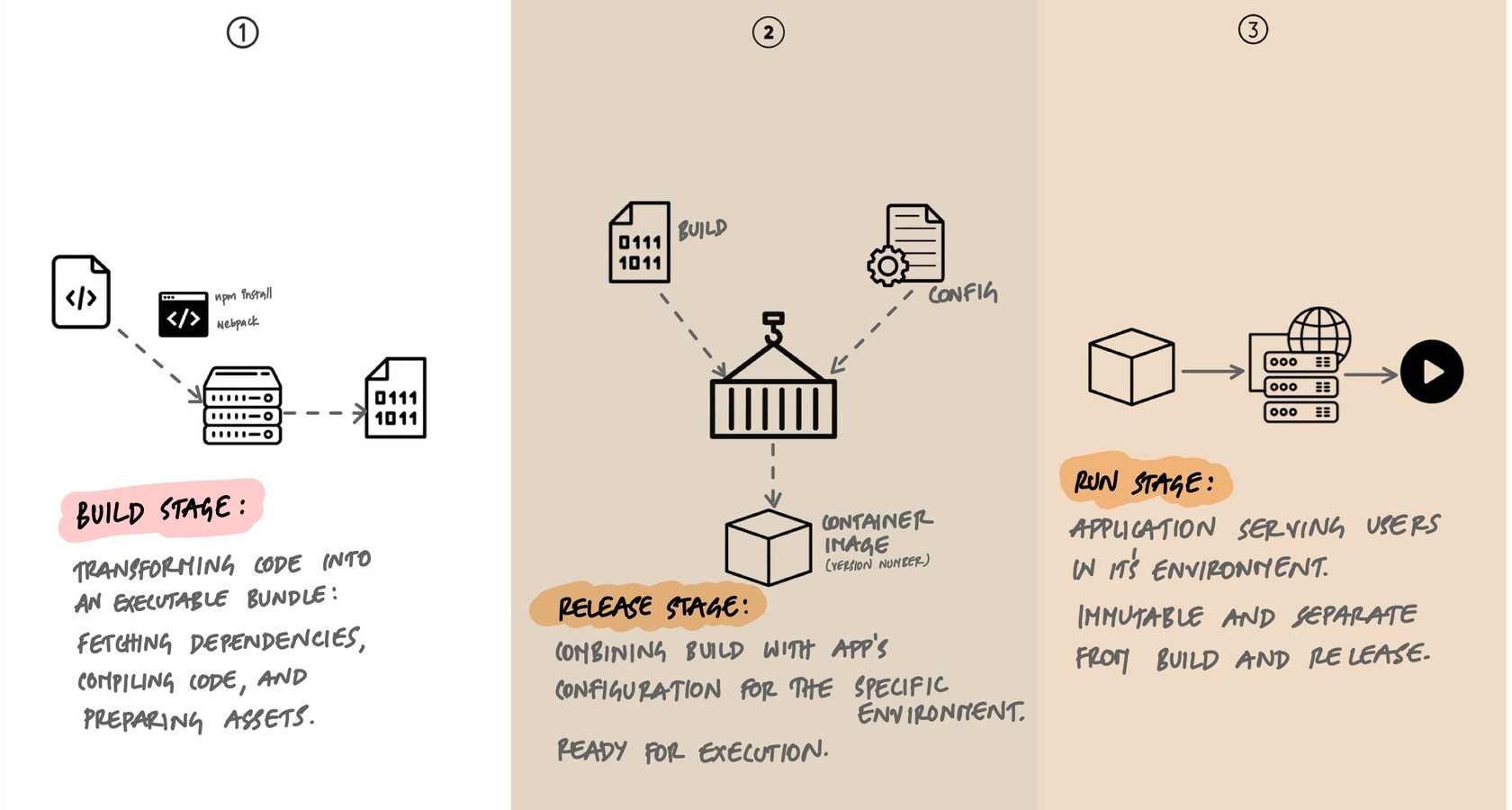

Three Stages of App Deployment: Build, Release, and Run

I've seen teams where "deploying" meant a sequence of manual steps - install dependencies, edit config files, restart processes - all tangled together. When something broke, the question was always the same: "What changed?" And the answer was always unclear, because the build, the configuration, and the process restart were mixed into one ad-hoc sequence. When our team separated deployment into three distinct stages - build, release, run - those problems disappeared. Not because the code got better, but because the process became predictable.

Why Three Stages?

The 12-factor app methodology defines a strict separation between three deployment stages: build, release, and run. This isn't arbitrary. Each stage has a different purpose, runs at a different time, and is triggered by different events. Mixing them together is the root cause of most deployment problems - inconsistent environments, unreproducible bugs, impossible rollbacks.

When they're properly separated, each stage becomes simple, predictable, and independently verifiable. The build produces an artifact. The release combines that artifact with configuration. The run executes the release. Nothing more.

Build: Turn Code into an Artifact

The build stage takes a specific version of source code and transforms it into an executable artifact. This means fetching dependencies, compiling code if needed, running any pre-processing steps, and packaging everything into a single, self-contained unit.

The key principle: a build is triggered by a developer (or a CI system) and produces exactly one artifact from exactly one commit. No environment-specific configuration is baked in. No secrets. No database URLs. Just the application code and its dependencies, packaged and ready.

# A typical build stage in a Dockerfile

FROM python:3.12-slim AS build

WORKDIR /app

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

COPY . .

RUN python -m compileall .

# The output: a container image with code + dependencies

# No config, no secrets, no environment-specific valuesWhat makes a build artifact useful is what it does not contain. There are no database connection strings, no API keys, no feature flags. The same artifact will eventually run in staging, production, and every other environment. If you bake production secrets into the build, you can't safely deploy that artifact to staging. If you bake the staging database URL in, the artifact is useless in production. A clean build is environment-agnostic.

In practice, build artifacts take different forms depending on the stack: Docker images, Python wheels, compiled binaries, or bundled archives. What matters is that the artifact is versioned (tied to a specific commit), immutable (never modified after creation), and stored somewhere retrievable (a container registry, artifact repository, or S3 bucket).

Release: Combine Artifact with Configuration

The release stage takes a build artifact and pairs it with environment-specific configuration to produce a release. A release is the complete, ready-to-run package: the code, its dependencies, and the configuration that tells it which database to connect to, which API keys to use, and which feature flags to enable.

# Release = Build artifact + Environment configuration

#

# Build artifact (same for all environments):

# myapp:v2.4.1 (Docker image from commit abc123)

#

# Staging config:

# DATABASE_URL=postgresql://dev:dev@staging-db:5432/myapp

# LOG_LEVEL=debug

# FEATURE_NEW_CHECKOUT=true

#

# Production config:

# DATABASE_URL=postgresql://app:secret@prod-db:5432/myapp

# LOG_LEVEL=warning

# FEATURE_NEW_CHECKOUT=false

#

# Two different releases from the same build artifactThis is the insight that makes the whole system work: the same build artifact produces different releases depending on which configuration you pair it with. Staging release and production release share identical code. The only difference is the environment variables.

Every release gets a unique identifier - typically a sequential number (v1, v2, v3) or a timestamp (2025-01-29T14:30:00). This identifier is permanent. Release v42 always refers to the same build artifact with the same configuration. You can inspect it, compare it to v41, or roll back to it six months later with full confidence that you're getting exactly what ran before.

Run: Execute the Release

The run stage takes a release and executes it in the target environment. Processes start, the application begins serving requests, and background workers pick up jobs. This stage should be as simple and automated as possible.

# Run stage: launch the release

# In Kubernetes, this is a deployment manifest

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: myapp

spec:

replicas: 3

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: myapp

image: registry.example.com/myapp:v2.4.1

envFrom:

- configMapRef:

name: myapp-production-config

- secretRef:

name: myapp-production-secretsThe run stage is the wrong place for complexity. It should not compile code, install dependencies, run database migrations, or fetch configuration from remote sources. All of that belongs in build or release. The run stage does one thing: start the processes defined in the release.

This matters because the run stage is where failures have the highest impact. If a process crashes at 3 AM, the orchestrator (Kubernetes, systemd, a process manager) needs to restart it automatically. That restart should be fast and deterministic - pull the release, start the process. If the run stage depends on downloading dependencies or compiling assets, a restart that should take seconds takes minutes, and a dependency registry outage means your application can't recover at all.

Why Strict Separation Matters

The three stages seem obvious when you describe them in isolation. But in practice, teams constantly blur the boundaries. Here are the most common violations and why they hurt:

Building in the Run Stage

Running pip install or npm install at container startup means your run stage depends on a package registry being available. If PyPI goes down or a package version is yanked, your application can't restart. You've turned an infrastructure problem into an application outage. Install dependencies in the build stage, not the run stage.

Baking Config into the Build

Hardcoding DATABASE_URL or API keys into your build artifact means you need a separate build for each environment. You can't promote the same artifact from staging to production. You lose the guarantee that what you tested is what you deploy. Keep configuration out of the build and inject it at the release stage.

Modifying Running Code

SSH-ing into a production server to edit files, patch code, or tweak configuration is the ultimate stage violation. The running instance now differs from the release it was deployed from. No one knows the actual state of production. The next deployment overwrites whatever was changed. If you need to fix something, go back to the beginning: change the code, build a new artifact, create a new release, deploy it.

Immutable Releases and Rollbacks

When releases are immutable - once created, never modified - rollbacks become trivial. Rolling back isn't a special operation. It's just deploying a previous release.

# Current state: running release v45

# Something is wrong. Roll back to v44.

# With immutable releases, this is a one-liner:

kubectl set image deployment/myapp myapp=registry.example.com/myapp:v44

# Or with Helm:

helm rollback myapp 44

# v44 is exactly what it was when it was first deployed.

# Same artifact, same config, same behavior. No surprises.Compare this to a world without immutable releases. "Rolling back" means figuring out which commit was deployed, rebuilding it (hoping the same dependencies are still available), reapplying configuration (hoping you remember what it was), and deploying the result (hoping it behaves the same). That's not a rollback - it's a new, untested deployment under pressure.

Immutable releases also make auditing straightforward. Every release is a record: this artifact, with this configuration, deployed at this time. You can answer "what was running in production last Tuesday at 2 PM?" with certainty, not guesswork.

What This Looks Like in CI/CD

A well-structured CI/CD pipeline maps directly to the three stages. Here's a simplified example:

# .github/workflows/deploy.yml

name: Build, Release, Run

on:

push:

branches: [main]

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Build Docker image

run: docker build -t myapp:${GITHUB_SHA::7} .

- name: Push to registry

run: docker push registry.example.com/myapp:${GITHUB_SHA::7}

release:

needs: build

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Create release tag

run: |

# Tag the build with a release number

docker tag myapp:${GITHUB_SHA::7} myapp:v${GITHUB_RUN_NUMBER}

docker push registry.example.com/myapp:v${GITHUB_RUN_NUMBER}

deploy:

needs: release

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Deploy to production

run: |

kubectl set image deployment/myapp \

myapp=registry.example.com/myapp:v${GITHUB_RUN_NUMBER}Each job maps to a stage. The build job produces an artifact from a commit. The release job tags it with a version. The deploy job runs it in the target environment. If any stage fails, the later stages don't execute. If production breaks, you roll back to a previous release tag.

Where Migrations Fit

Database migrations are the one piece that doesn't fit neatly into the three stages, and teams handle them differently. The common approaches:

- Run migrations as a separate job before deploy. After the release is created but before the run stage starts, a migration job runs against the target database. This keeps migrations out of the run stage while ensuring the schema is ready before traffic arrives.

- Run migrations at application startup. Some frameworks (Django, Rails) support running migrations when the process starts. This is simpler but risky with multiple replicas - two pods might try to run the same migration simultaneously.

- Treat migrations as their own pipeline. In larger systems, schema changes are deployed independently of application code. The migration runs first, the application code that uses the new schema deploys later. This requires backward-compatible migrations but gives the most control.

The important thing is that migrations have a clear home. They shouldn't be something you SSH in and run manually on production Friday afternoon.

Key Takeaway

Build, release, run is not just a deployment model - it's a way of thinking about the path from code to production. The build stage is where complexity is allowed: dependency resolution, compilation, asset processing. The release stage is where environment specificity enters: configuration, secrets, feature flags. The run stage is where simplicity is required: start the process, serve traffic. Keep these stages distinct, make releases immutable, and you get deployments that are reproducible, auditable, and trivially reversible. Every time you catch yourself blurring the boundaries - installing packages at startup, hardcoding config, hotfixing production - that's a sign the stages need cleaner separation.