The Stateless Processes

We have seen applications that worked fine with a single server suddenly break when scaled to two. Users would log in, make a request, get a response, make another request - and be asked to log in again. The session data was stored in the application's memory. The second request hit a different server. That server had no idea who the user was. The application was stateful, and scaling it exposed that problem instantly.

What Stateless Actually Means

A stateless process doesn't remember anything between requests. Each request arrives with everything the process needs to handle it - authentication tokens, session identifiers, request data - and the process doesn't store anything locally for the next request to use.

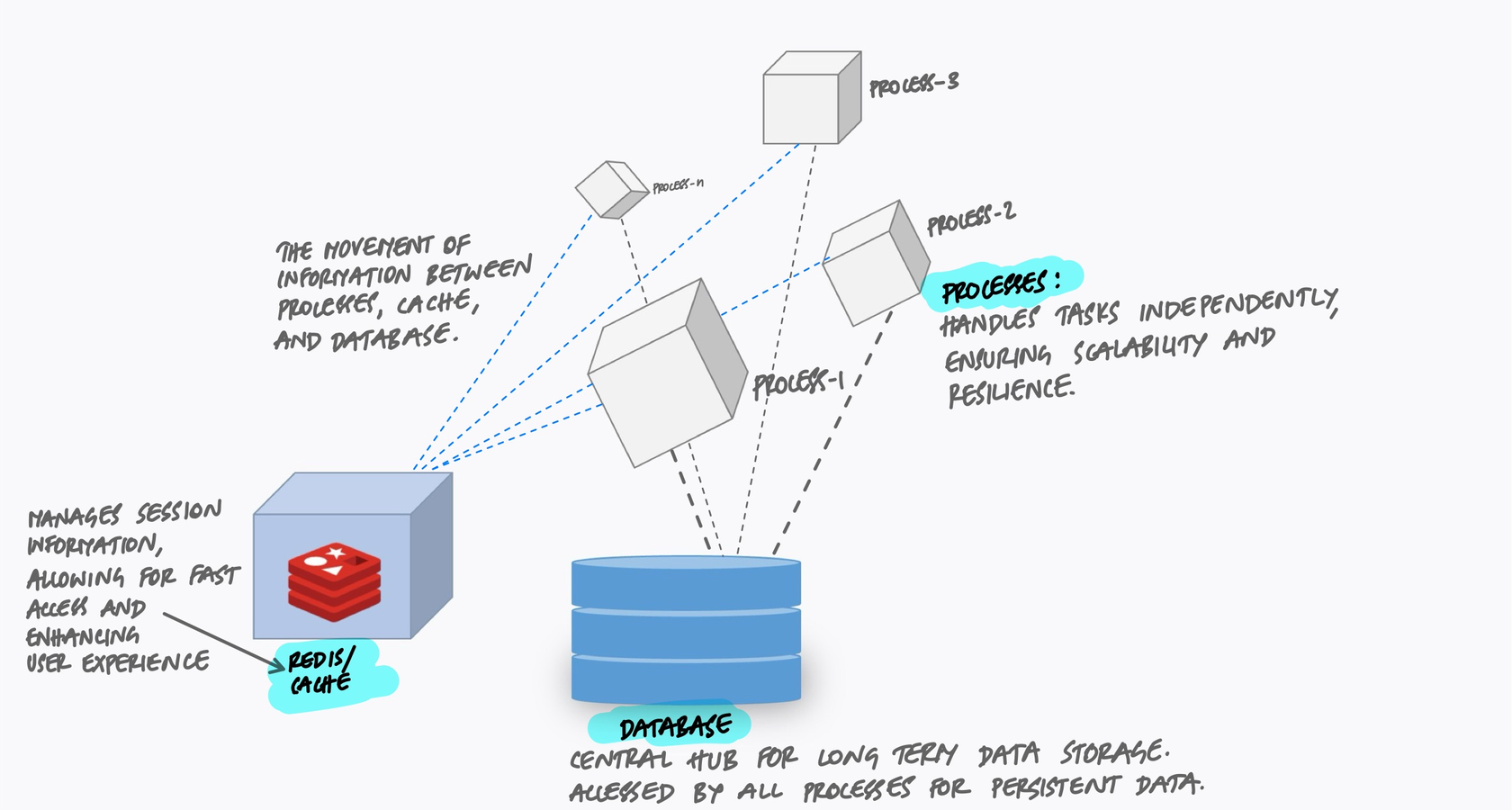

This doesn't mean your application has no state. Of course it does - users have sessions, shopping carts have items, dashboards have preferences. The point is that state lives in external services (databases, caches, object stores), not inside the application process itself. The process is a pipeline: data comes in, gets processed, results go out. Nothing sticks.

The 12-factor app methodology puts it simply: processes are stateless and share-nothing. Any data that needs to persist must be stored in a stateful backing service.

Why This Matters: The Scaling Problem

With a single process, stateful or stateless doesn't matter much. Everything is in one place. The problems begin when you need more than one process - and you will. Traffic grows, you add a second server, a load balancer distributes requests between them.

If your process stores state locally - user sessions in memory, uploaded files on the local disk, cached data in a local dictionary - then request A might hit server 1 and store some state, while request B hits server 2 and can't find it. The user sees broken behavior. Data disappears. Sessions vanish.

# This breaks when you scale to multiple processes

# In-memory session store — lives and dies with the process

sessions = {}

@app.route("/login", methods=["POST"])

def login():

user = authenticate(request.form)

session_id = generate_session_id()

sessions[session_id] = {"user_id": user.id} # stored in THIS process

return jsonify({"token": session_id})

@app.route("/profile")

def profile():

session_id = request.headers.get("Authorization")

session = sessions.get(session_id) # fails if different process

if not session:

return jsonify({"error": "unauthorized"}), 401

return get_user_profile(session["user_id"])This code works perfectly with one process. Add a second process behind a load balancer and it breaks immediately. The login request stores the session in process A's memory. The profile request lands on process B, which has no record of that session. The user gets a 401 error.

Moving State Out

The fix is to move all state into external services that every process can access. Sessions go into Redis. Uploaded files go into object storage. Cached data goes into a shared cache. The processes become stateless - interchangeable workers that can be started, stopped, or replaced without losing anything.

# This works with any number of processes

import redis

# Session store lives outside the process — shared by all

session_store = redis.Redis.from_url(os.environ["REDIS_URL"])

@app.route("/login", methods=["POST"])

def login():

user = authenticate(request.form)

session_id = generate_session_id()

session_store.setex(

session_id,

3600, # expires in 1 hour

json.dumps({"user_id": user.id})

)

return jsonify({"token": session_id})

@app.route("/profile")

def profile():

session_id = request.headers.get("Authorization")

data = session_store.get(session_id) # works from any process

if not data:

return jsonify({"error": "unauthorized"}), 401

session = json.loads(data)

return get_user_profile(session["user_id"])The only change: sessions are stored in Redis instead of a local dictionary. Now it doesn't matter which process handles which request. They all read from and write to the same external store. You can run 2 processes or 200 - the behavior is identical.

The Sticky Session Trap

Some teams try to solve the stateful process problem with sticky sessions. The load balancer remembers which server handled a user's first request and routes all subsequent requests to the same server. This way, the in-memory session is always available.

This works until it doesn't. Sticky sessions create several problems:

- Uneven load distribution. Some servers end up with more "sticky" users than others. You can't rebalance without breaking sessions.

- Deploys break sessions. When you restart a server to deploy new code, every user stuck to that server loses their session.

- Scaling down loses data. When you remove a server to save costs during low traffic, every user on that server gets logged out.

- Server crashes lose state. If a server dies unexpectedly, all sessions on it are gone. No recovery possible.

Sticky sessions are a band-aid on a design problem. They let you avoid fixing the real issue - stateful processes - by adding complexity at the load balancer layer. The proper fix is to move state out of the process entirely.

Common State That Needs to Move

Sessions are the most obvious example, but they're not the only state that sneaks into processes. Here are the common ones:

Uploaded Files

When a user uploads a file and your application saves it to the local disk, that file only exists on one server. If the next request hits a different server, the file isn't there. If the server is replaced, the file is gone.

Move uploaded files to object storage (S3, Google Cloud Storage, MinIO) immediately after receiving them. The application saves the file to the external store and keeps only a reference (the URL or key) in the database.

# Bad: saving to local disk

@app.route("/upload", methods=["POST"])

def upload_bad():

f = request.files["photo"]

f.save(f"/uploads/{f.filename}") # only on THIS server

return jsonify({"status": "saved"})

# Good: saving to object storage

@app.route("/upload", methods=["POST"])

def upload_good():

f = request.files["photo"]

key = f"uploads/{uuid4()}/{f.filename}"

s3.upload_fileobj(f, bucket, key) # accessible from ANY server

return jsonify({"url": f"https://{bucket}.s3.amazonaws.com/{key}"})In-Process Caches

A dictionary used as a cache inside your process is invisible to other processes. Each process builds its own cache independently, wasting memory and producing inconsistent results. A user might see stale data on one request and fresh data on the next, depending on which process handles it.

Use a shared cache like Redis or Memcached. Every process reads from and writes to the same cache, so the data is consistent and the memory is used efficiently.

Temporary Files

Processing a large file - resizing an image, generating a PDF, parsing a CSV - often involves writing to a temporary location. This is fine as long as the temporary file is used and discarded within the same request. The problem comes when one request writes a temp file and a later request expects to find it. With multiple processes, there's no guarantee the same process will handle both requests.

The rule: temporary files are fine for the duration of a single request. Anything that needs to survive beyond that request must go into an external store.

What You Get from Statelessness

When your processes are truly stateless, several things become easy that were previously hard:

- Horizontal scaling. Need more capacity? Start more processes. They're all identical and interchangeable. No coordination needed.

- Zero-downtime deploys. Start new processes with the updated code, then stop the old ones. No sessions are lost, no uploads disappear, no state needs to be migrated.

- Crash recovery. A process dies? The orchestrator starts a new one. Since no state was lost (it was all in external services), the new process picks up where any process could.

- Simpler debugging. Every process behaves the same way. You don't get bugs that only happen on "server 3" because server 3 has different cached data than server 1.

The Mindset Shift

Stateless processes require a shift in how you think about your application. Instead of treating each process as a long-running entity with its own memory and history, treat it as disposable. It could be killed and replaced at any moment, and nothing of value should be lost.

A good test: if you restart every process in your application simultaneously, does anything break beyond the brief interruption? If users lose their sessions, if uploaded files vanish, if cached data disappears and can't be rebuilt - those are signs of state living where it shouldn't be.

Key Takeaway

Stateless doesn't mean your application has no state. It means state doesn't live inside your processes. Sessions go in Redis. Files go in object storage. Cached data goes in a shared cache. The processes themselves are empty vessels - they receive a request, do the work, store the results externally, and move on. This is what makes them disposable, scalable, and reliable. The moment you store something in a local variable, a local file, or in-process memory that another request might need, you've created a coupling between requests and processes. That coupling is invisible until you scale, and then it breaks everything at once.