The Dev/Prod Parity

We have seen teams spend days debugging production issues that worked perfectly in development. For example, in a hypothetical scenario, user searches with special characters return empty results - the root cause being SQLite locally and PostgreSQL in production, handling LIKE queries with Unicode characters differently. A five-minute fix hidden behind a two-day investigation, all because the development environment was quietly lying about how the application actually behaved.

What Dev/Prod Parity Actually Means

The idea is straightforward: your development environment should behave like production. Not just look similar - actually behave the same way. When you run your application locally and it works, that should give you genuine confidence that it will work in production too.

The 12-factor app methodology calls this "dev/prod parity" and treats it as a first-class principle. The goal is to keep the gap between development and production as small as possible, across three dimensions: time, people, and tools.

When these gaps are wide, you get the most dreaded phrase in software: "works on my machine."

The Three Gaps

The Time Gap

The time gap is how long code sits between being written and being deployed. In some teams, developers write code that doesn't reach production for weeks or months. By then, the developer has moved on to other work, the codebase has changed underneath them, and the context needed to debug issues is long gone.

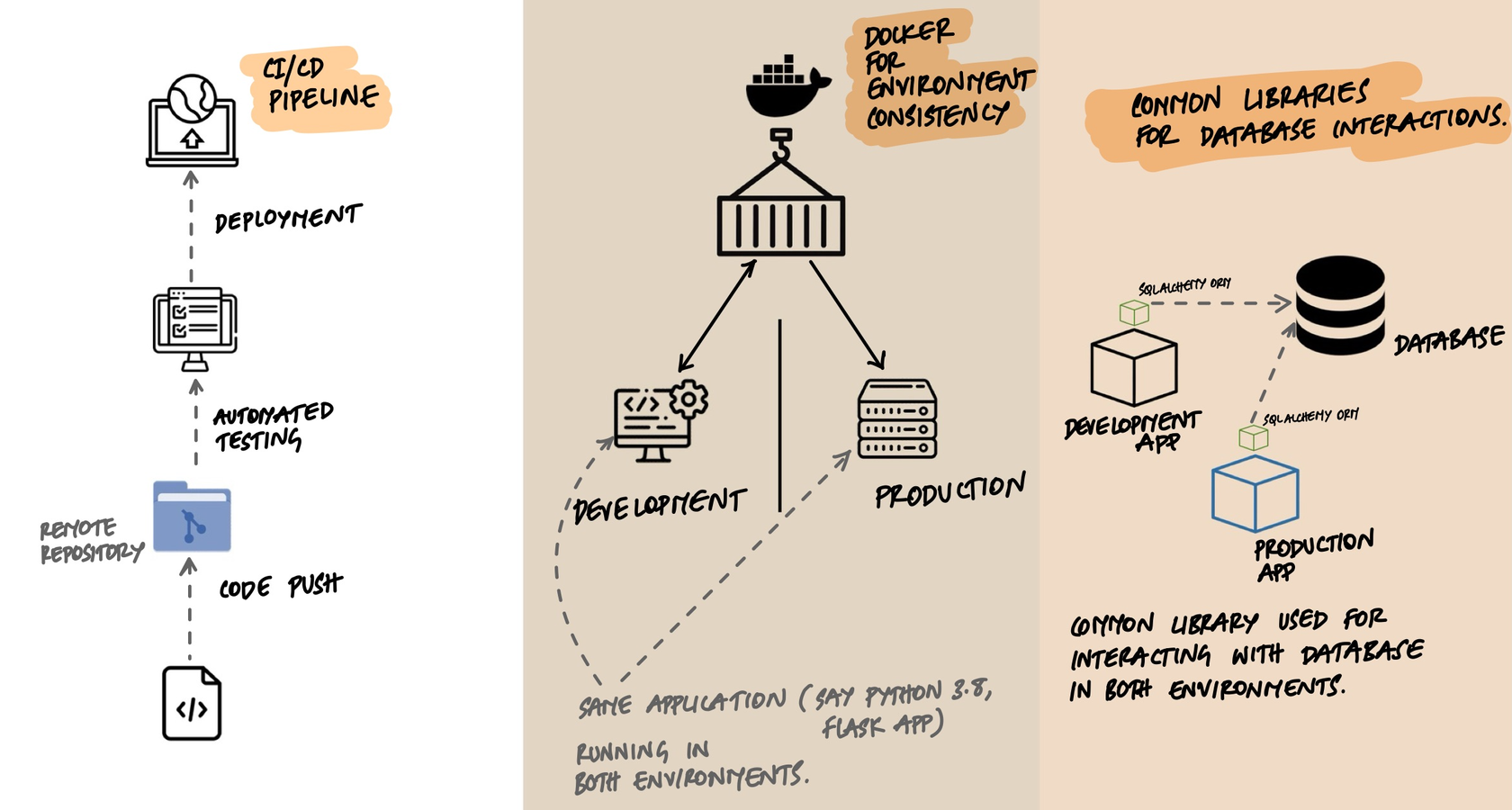

Shrinking this gap means deploying frequently - ideally within hours of writing code. CI/CD pipelines automate this: every push triggers tests, and successful builds can be deployed automatically or with a single approval. The shorter the feedback loop, the easier it is to connect a production problem to the code that caused it.

The Personnel Gap

In traditional setups, developers write code and a separate operations team deploys it. The developers don't fully understand the production environment, and the ops team doesn't fully understand the code. When something breaks, each side points at the other.

The fix is shared ownership. Developers who deploy their own code develop an intuition for production behavior. They write code differently when they know they'll be the ones woken up at 3 AM if it breaks. This is the core insight behind DevOps - not a job title, but a mindset where writing code and running code are one continuous responsibility.

The Tools Gap

This is the sneakiest gap and where most teams get burned. A developer uses SQLite on their laptop, but production runs PostgreSQL. The application uses the local file system for uploads, but production uses S3. Tests run against an in-memory cache, but production uses Redis.

Each of these differences is a lie your development environment tells you. Your code "works" locally, but it's working against a different system than the one it'll face in production. The behavior is similar enough to build false confidence, but different enough to cause real bugs.

Where the Tools Gap Actually Bites

The tools gap isn't theoretical. Here are real differences that have caused production bugs:

SQLite vs PostgreSQL

- SQLite is case-insensitive for string comparisons by default. PostgreSQL is case-sensitive. A query that finds "John" when you search for "john" locally will return nothing in production.

- SQLite doesn't enforce string length. You can insert 1000 characters into a

VARCHAR(50)column without error. PostgreSQL will reject it. - Date handling, JSON operators, and transaction isolation all differ. An ORM hides most of this, but not all of it.

Local File System vs S3

- File paths on macOS are case-insensitive. On Linux and S3,

Avatar.pngandavatar.pngare different files. Code that works on your Mac silently breaks in production. - Local file operations are synchronous and essentially instant. S3 operations are network calls that can fail, time out, or behave differently under load.

In-Memory State vs Redis

- An in-memory dictionary in your dev process has no serialization step. Redis serializes everything. Objects that work fine in memory can fail when Redis tries to serialize and deserialize them.

- Redis has eviction policies. Your local dictionary doesn't. A cache that "always works" in development quietly loses keys under memory pressure in production.

The pattern is always the same: the development tool is simpler and more forgiving than the production tool. Bugs hide in the differences.

Docker Changed Everything

Before containers, matching dev and prod environments was genuinely hard. You'd write installation scripts, maintain wikis with setup instructions, and still end up with "works on my machine" problems because someone had a different Python version or a missing system library.

Docker solved this by packaging the entire runtime environment - OS, libraries, language version, system tools - into an image. The same image runs on a developer's laptop, in CI, and in production.

# docker-compose.yml — run real backing services locally

version: "3.8"

services:

app:

build: .

ports:

- "8000:8000"

environment:

- DATABASE_URL=postgresql://dev:dev@db:5432/myapp

- REDIS_URL=redis://cache:6379/0

- S3_ENDPOINT=http://minio:9000

depends_on:

- db

- cache

- minio

db:

image: postgres:16

environment:

- POSTGRES_USER=dev

- POSTGRES_PASSWORD=dev

- POSTGRES_DB=myapp

cache:

image: redis:7-alpine

minio:

image: minio/minio

command: server /data

environment:

- MINIO_ROOT_USER=minioadmin

- MINIO_ROOT_PASSWORD=minioadminNotice what this gives you: real PostgreSQL instead of SQLite. Real Redis instead of an in-memory dictionary. Real S3-compatible storage (MinIO) instead of the local file system. Your docker-compose file is where parity becomes practical. Instead of mocking backing services, you run real instances of them locally. Your development PostgreSQL behaves like your production PostgreSQL because it is PostgreSQL - same engine, ideally the same major version.

The Database Trap

The most common parity violation - and the most dangerous - is using a different database in development than in production. This deserves special attention because it's so tempting and so harmful.

SQLite is lightweight, needs no setup, and stores everything in a single file. It's the perfect development database... until it isn't. Every ORM will tell you it abstracts away database differences. That's mostly true for basic CRUD operations. It falls apart for:

- Complex queries with database-specific behavior (window functions, CTEs, recursive queries)

- Migrations that rely on database-specific features (column type changes, concurrent index creation)

- Concurrent writes - SQLite locks the entire database file, while PostgreSQL handles row-level locking

- Performance patterns - what's fast in SQLite can be slow in PostgreSQL, and vice versa

The solution: run the same database engine in development. With Docker, this is a one-line addition to your docker-compose file. The small cost in setup time pays for itself the first time you avoid a "works locally but breaks in production" bug.

Environment Variables: The Parity Bridge

Dev/prod parity doesn't mean identical environments - it means environments that behave the same way. The differences between environments (database host, API keys, feature flags) should live in configuration, not in code.

# app.py — same code runs in every environment

import os

from flask import Flask

from flask_sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

app = Flask(__name__)

# The database URL comes from the environment, not the code.

# Development: postgresql://dev:dev@localhost:5432/myapp

# Production: postgresql://app:secret@prod-db:5432/myapp

# Same engine, same behavior, different host.

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI"] = os.environ["DATABASE_URL"]

db = SQLAlchemy(app)

class User(db.Model):

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

username = db.Column(db.String(80), unique=True, nullable=False)

@app.route("/")

def index():

users = User.query.all()

return {"users": [u.username for u in users]}The application code is identical across environments. The only thing that changes is the environment variables. And because both development and production use PostgreSQL, the ORM queries, the migration scripts, and the edge cases all behave the same way. No surprises at deploy time.

What Good Parity Looks Like

A practical checklist:

- Same database engine in development and production, ideally the same major version.

- Same message broker - if production uses RabbitMQ, don't use an in-memory queue in development.

- Same cache - if production uses Redis, run Redis locally too.

- Containerized development with docker-compose, so every developer gets the same environment with one command.

- CI runs the same containers as production, so your test environment matches too.

- Configuration via environment variables so switching between environments means changing a

.envfile, not editing code.

When Perfect Parity Is Impractical

Being realistic: perfect parity isn't always possible or necessary. You probably don't need a multi-node Elasticsearch cluster in development. You don't need to replicate your CDN locally. You don't need production-scale hardware.

The question to ask is: where do differences in behavior cause bugs? That's where parity matters. Differences in scale or performance are usually fine - your laptop is slower than a production cluster, and that's OK. Differences in behavior are not - if your local search engine handles queries differently than production, that's where bugs hide.

Focus parity efforts on the components most likely to behave differently: databases, caches, message brokers, and file storage. For everything else, use your judgment.

Key Takeaway

Dev/prod parity is about eliminating the lies your development environment tells you. Every difference between development and production is a place where bugs can hide - where code that "works" locally will fail when it faces real infrastructure. The three gaps (time, people, tools) each contribute to this problem. CI/CD shrinks the time gap. Shared ownership shrinks the personnel gap. Docker and running real backing services locally shrinks the tools gap. You don't need perfect parity everywhere, but you do need it where behavioral differences cause bugs. The goal isn't identical environments - it's honest environments, where "it works on my machine" actually means something.