The Codebase Principle

Earlier, it was common for production codebases to drift far from development. Hotfixes were applied directly to servers. Features lived in branches for months. The "real" code existed in three different places, and no one could say which version was authoritative. Every deploy felt like a gamble. To solve this, the 12-factor methodology introduced a deceptively simple rule: one codebase, tracked in version control, deployed everywhere.

The Rule: One Codebase, Many Deploys

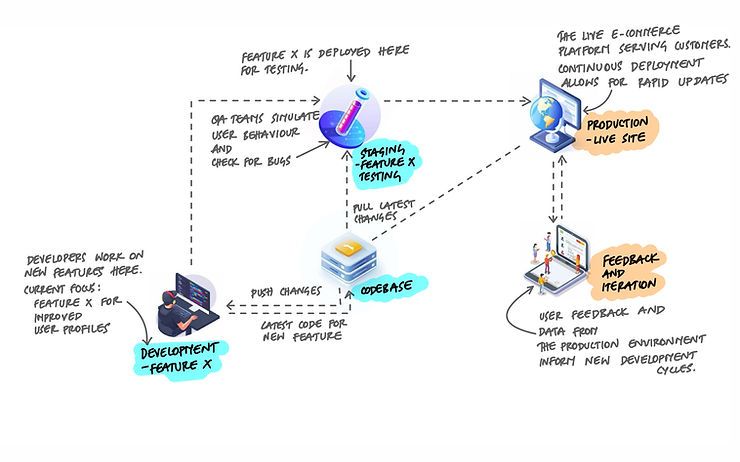

The 12-factor app methodology starts with a simple rule: every application has exactly one codebase, tracked in version control, and that codebase produces every deploy. Development, staging, production, a teammate's local environment - they all run code from the same repository. The only differences between deploys are configuration values like database URLs, API keys, and feature flags. Never the code itself.

This sounds obvious, but it's violated constantly. And when it's violated, the problems are subtle at first and painful later.

What Violating This Looks Like

The codebase principle gets broken in several ways, and each one creates a different kind of pain:

Copy-Paste Repos

A team needs a second version of an application - maybe for a different client, or a different region. Instead of configuring the existing app differently, they copy the entire repository and start making changes. Now there are two codebases. Bug fixes in one don't reach the other. Features diverge. Within months, the two repos share 90% of their code but are maintained independently. Every change has to be made twice, and half the time it isn't.

Production Hotfixes

Something breaks in production at 2 AM. A developer SSH-es into the server and edits a file directly. The fix works. Everyone goes back to sleep. But the fix was never committed to the repository. The next deploy overwrites it. The bug returns. Or worse - the hotfix stays on the server, and now production is running code that doesn't exist anywhere in version control. No one can reproduce the production environment because no one knows what's actually running.

Long-Lived Branches

A feature branch lives for three months. During that time, the main branch keeps moving. The feature branch falls further behind. When it's finally time to merge, the conflicts are massive. The branch has effectively become a separate codebase - it shares an origin with main but has diverged so far that merging feels like integrating two different applications.

Environment-Specific Code Paths

Code that checks which environment it's in and behaves differently:

# This is a code smell — the codebase should be identical

# across environments. Only configuration should differ.

if os.environ.get("ENVIRONMENT") == "production":

# production-only logic

send_real_email(user, message)

else:

# staging/dev shortcut

log_email_to_console(user, message)This looks harmless but it means the code running in staging is not the same code running in production. You're no longer testing what you deploy. The right approach is to make email delivery a configurable service - swap the implementation via configuration, not conditional logic in the code.

# Better: same code path, different config

# mail.py

def get_mailer():

backend = os.environ.get("MAIL_BACKEND", "console")

if backend == "smtp":

return SmtpMailer(os.environ["SMTP_URL"])

return ConsoleMailer()

# usage — identical in every environment

mailer = get_mailer()

mailer.send(user, message)Now the code path is identical everywhere. The only thing that changes is the MAIL_BACKEND environment variable. You test exactly what you deploy.

How Deploys Differ

If the code is the same everywhere, what makes staging different from production? Configuration. Each deploy is a running instance of the same codebase at a particular commit, combined with environment-specific settings.

# Same codebase, same commit, different config

# Staging (.env.staging)

DATABASE_URL=postgresql://dev:dev@staging-db:5432/myapp

MAIL_BACKEND=console

LOG_LEVEL=debug

FEATURE_NEW_CHECKOUT=true

# Production (.env.production)

DATABASE_URL=postgresql://app:secret@prod-db:5432/myapp

MAIL_BACKEND=smtp

LOG_LEVEL=warning

FEATURE_NEW_CHECKOUT=falseStaging might be a few commits ahead of production. A developer's laptop might be running a feature branch. But the principle holds: the code comes from one repository, and the differences are in configuration, not in the source.

One Codebase Per App, Not Per System

The principle says one codebase per app, not one codebase for your entire system. If you have a web frontend, an API backend, and a background worker, those can be three separate codebases - three separate apps. Each one follows the one-codebase rule independently.

What you should not have is one app spread across multiple repositories. If deploying your API requires pulling code from three different repos and stitching them together, that's a violation. The API should live in one repo.

When multiple apps share common functionality, the shared code should be extracted into a library - a package that each app declares as a dependency. Copying shared code between repositories is the same trap as copy-paste repos: it creates divergence that gets worse over time.

# Shared code becomes a package, not copied files

# requirements.txt for the API

flask==3.0.0

mycompany-shared-auth==1.4.2 # internal package

mycompany-shared-models==2.1.0 # internal package

# requirements.txt for the worker

celery==5.3.0

mycompany-shared-auth==1.4.2 # same package, same version

mycompany-shared-models==2.1.0 # same package, same versionBoth apps depend on the shared packages. When the auth logic changes, the package is updated once, and both apps pick up the new version through their dependency declarations. No copy-pasting, no drift.

Branching Without Diverging

Version control makes it easy to create branches. The danger is letting branches live too long. A branch that exists for a day is a lightweight collaboration tool. A branch that exists for three months is a separate codebase in disguise.

Trunk-based development keeps branches short-lived. Developers create small feature branches, merge them into main within a day or two, and deploy frequently. This keeps the codebase unified and reduces the pain of integration.

# Short-lived branches keep the codebase unified

# Create a branch, do the work, merge quickly

git checkout -b feature/add-password-reset

# ... make changes, commit ...

git push origin feature/add-password-reset

# open a pull request, get it reviewed, merge within 1-2 days

# For larger features, use feature flags instead of branches

FEATURE_PASSWORD_RESET=false # deployed but hidden

FEATURE_PASSWORD_RESET=true # enabled when readyFor features too large to merge in a day, feature flags are a better solution than long-lived branches. The code is merged into main and deployed, but the feature is hidden behind a flag until it's ready. The codebase stays unified. No divergence.

The Confidence Test

Here is a quick way to check if your team follows the codebase principle:

Can any developer clone the repository, set the right environment variables, and have a working application - identical to what runs in production?

If the answer is yes, the codebase principle is working. If the answer involves "you also need to grab these files from the staging server" or "production has a few patches that aren't in the repo" or "check the wiki for the special build steps" - those are signs of drift.

Key Takeaway

One codebase, tracked in version control, deployed everywhere. This is the starting point for everything else in the 12-factor methodology. If your staging environment runs different code than production, you can't trust your tests. If hotfixes bypass the repository, you can't reproduce bugs. If feature branches live for months, you don't have one codebase - you have several. The principle is deceptively simple: all deploys come from the same source. The differences between environments are configuration, not code. When this holds, deploying becomes predictable. When it doesn't, every deploy is a surprise.