Silence, Stories, and Strategies: The Jeff Bezos Method for Transforming Dialogue in the Boardroom

Meetings work best when everyone walks in prepared. That sounds obvious, but think about how rarely it actually happens. In my work, meetings and brainstorming sessions are a big part of getting things done. But there's a pattern I keep running into: the first 20 minutes disappear on context-setting. Someone walks through a slide deck, reading bullet points aloud while everyone else half-listens. By the time the "discussion" starts, people are either checked out or scrambling to form an opinion on something they just heard for the first time. The meeting ends, and you walk away wondering what was actually decided.

Then I came across Carmine Gallo's "The Bezos Blueprint," which looks at Jeff Bezos's shareholder letters and how meetings actually work at Amazon. One idea in particular stuck with me - not because it was complicated, but because it was so simple that it made me wonder why everyone isn't doing it already. This post is about that idea.

Why Most Meetings Fail

Think about the last few meetings you attended. How many of them followed this pattern? Someone shares their screen, clicks through slides, and talks at the room. A few people ask questions. Most stay quiet. The meeting runs long, drifts off topic, and ends without anyone being entirely sure what was decided or who's doing what.

The deeper problem is that everyone is processing information in real time. They're hearing ideas for the first time as slides click by. There's no time to think critically, no foundation for genuine debate. So what you get instead is surface-level reactions and groupthink - people agreeing because they haven't had time to form a real opinion.

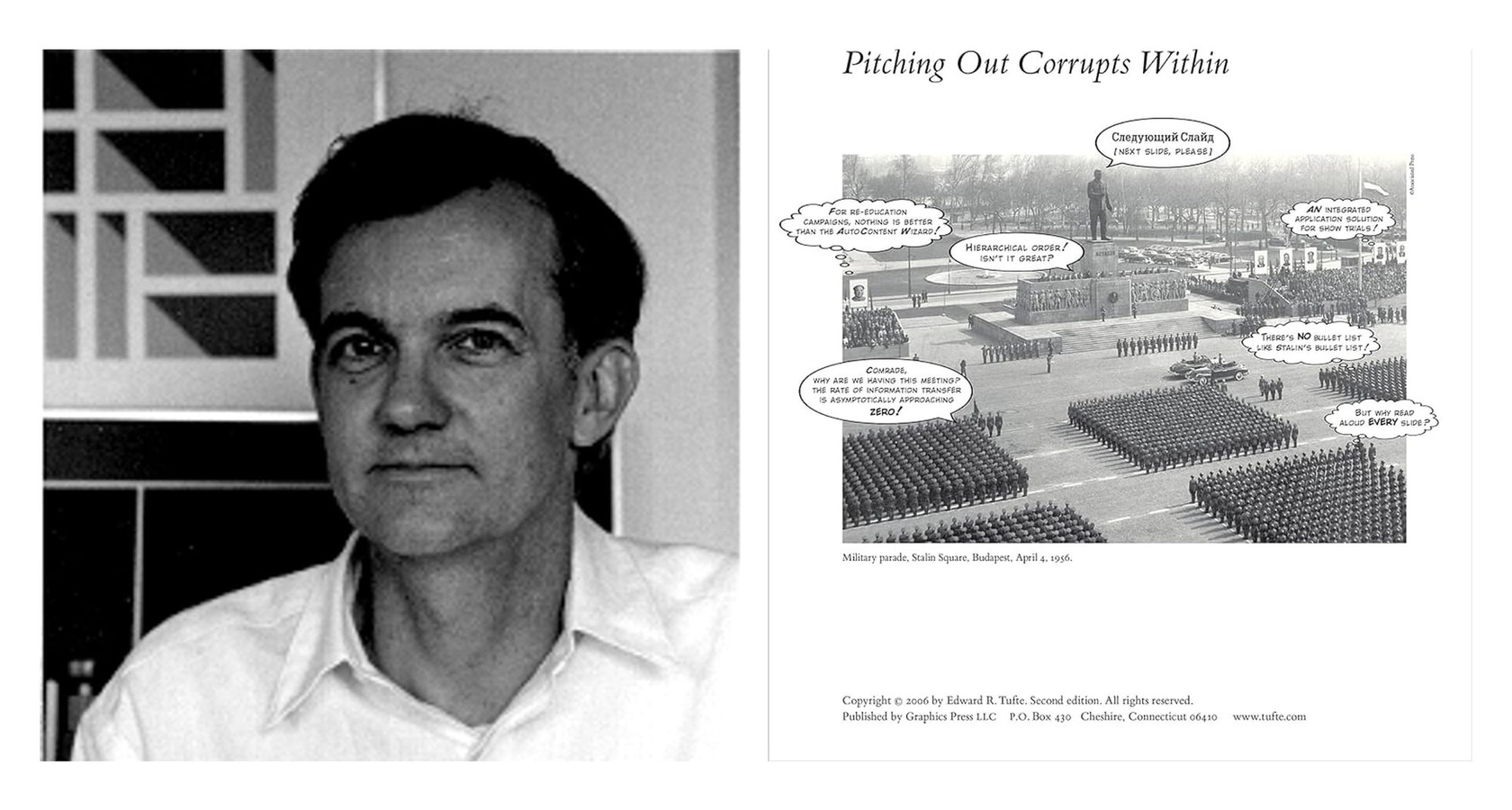

Edward Tufte, a statistician known for his work on information design, identified the root of this problem years ago in his essay "The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint." His argument comes down to this: the format itself is the issue. Slides force complex ideas into fragmented bullet points, stripping away nuance, context, and the logical connections between ideas. You end up with a presentation that looks organized but actually hides the holes in the thinking.

By playing around with Phluff rather than providing information, PowerPoint allows speakers to pretend that they are giving a real talk, and the audiences to pretend that they are listening. This prankish conspiracy against substance and thought should always provoke the question, 'Why are we having this meeting?'

Bezos's Solution: Write It Down

Bezos's fix was radical in its simplicity: ban PowerPoint. In its place, he required teams to write narrative memos - structured, 4 to 6 page documents that lay out an idea, a problem, or a proposal in complete sentences and paragraphs. Not bullet points. Not talking points. Full prose, with a logical argument that flows from start to finish.

Here's why this matters more than it seems. Writing in complete sentences forces you to actually think through what you're saying. You can hide fuzzy thinking behind a bullet point - a few vague words, an arrow, and everyone nods along. But try writing that same idea as a paragraph, and the gaps become obvious. If your logic doesn't hold up, the act of writing will expose it - to you, before anyone else even reads it.

That's the real insight. The memo isn't just a document for the meeting - it's a thinking tool for the writer. By the time it reaches the room, the ideas have already been stress-tested by the person who wrote them. The meeting starts at a much higher level because the hard thinking has already happened.

Full sentences are harder to write. They have verbs. The paragraphs have topic sentences. There is no way to write a six-page, narratively structured memo and not have clear thinking.

The Silent Start

This is the part that surprises people most. At the beginning of every Amazon meeting, nobody talks. Nobody presents. Everyone just sits in silence and reads the memo. For 20 to 30 minutes, a room full of senior executives does nothing but read.

It sounds strange, but think about what it solves. We've all been in meetings where someone says "as you saw in the pre-read..." and half the room clearly hasn't read it. The silent start eliminates that problem entirely. Everyone reads the same material, at the same time, in the same room. No pretending. No catching up while someone else is talking.

When the silence ends and the conversation starts, something different happens. People ask sharper questions. They challenge specific points in the memo. They build on each other's ideas instead of repeating what was already said. The quality of discussion is on a completely different level compared to what you get when people are reacting to slides in real time.

The Empty Chair

Bezos famously placed an empty chair in meetings to represent the customer. At first glance, it looks like a symbolic gesture. But in practice, it did something very specific: it kept every discussion anchored to the person who actually matters.

Meetings have a natural tendency to drift toward internal concerns - what's easier for us, what fits our timeline, what makes our team look good. The empty chair was a physical reminder to ask a different question: "What would the customer want?" It turned an abstract principle - customer obsession - into something concrete that sat right there in the room. You don't need to be Amazon to use this idea. Any team can benefit from a visible reminder of who they're ultimately serving.

Two-Pizza Teams

Bezos had a simple rule about meeting size: if two pizzas couldn't feed the group, the group was too big.

This wasn't about pizza - it was about what happens to conversations as groups grow. In a room of five or six people, everyone speaks. Everyone is accountable. In a room of fifteen, three people do most of the talking while everyone else becomes an audience. The two-pizza rule was a way to make sure meetings stayed small enough for real discussion - where every person present had a reason to be there and something to contribute.

Ending with Action

Every Amazon meeting ended with explicit next steps: who is doing what, by when. This sounds basic, but think about how many meetings you've been in that ended with everyone nodding, saying "sounds good," and then walking away without a clear idea of what happens next.

Bezos treated this as non-negotiable. A meeting without defined actions, owners, and deadlines wasn't a productive meeting - it was just a conversation. The action items turned the discussion into something that actually moved work forward.

How to Write a Narrative Memo

If you want to try this in your own team, here's a structure that works well. A good narrative memo isn't a report or a status update - it's a coherent argument written in plain prose. Think of it as making your case on paper, so the meeting can focus on debating the case rather than hearing it for the first time.

- Start with the purpose. What decision needs to be made, or what problem needs to be solved? State this clearly in the first paragraph. The reader should know within 30 seconds why they're reading this document.

- Provide context. Give the reader enough background to understand the situation, regardless of how familiar they are with the topic. This levels the playing field and prevents the "can someone explain what this is about?" question that derails so many meetings.

- Define the problem or opportunity. Be specific about what's at stake and why it matters now. Vague problem statements lead to vague discussions.

- Present your analysis. This is the core of the memo. Walk through the data, the research, the reasoning. Use evidence to build your argument, but don't bury the reader in numbers - use data to tell a story, not to overwhelm.

- Explore alternatives. Show that you've thought about other paths. What else could we do? What are the trade-offs? Being upfront about alternatives shows thorough thinking and pre-empts the "but have you considered..." questions that can derail a discussion.

- Make a recommendation. Based on your analysis, what should we do? Be decisive. A memo that lays out options without taking a position isn't helping anyone - it's just transferring the thinking to the reader.

- Define next steps. Who needs to do what, and by when? A memo that doesn't end with clear actions is just an essay.

If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough.

One more thing: write in plain language. If a sentence needs jargon or specialized knowledge to make sense, rewrite it. The whole point of a narrative memo is that it forces you to truly understand what you're proposing. And the clearest sign that you understand something is being able to explain it simply.

Key Takeaway

The next time you're in a meeting where someone is reading bullet points off a screen while the room quietly checks email, consider what Bezos figured out: the problem isn't that people don't care. It's that the format makes it nearly impossible to care. Slides encourage passive consumption. Your brain goes into "receive mode" instead of "think mode."

Narrative memos flip that. They demand active thinking - from the writer, who has to organize their thoughts into a coherent argument, and from the reader, who has to engage with that argument critically before saying a word. The meeting becomes a place for debate and decisions, not for information transfer.

You don't need to be Amazon to try this. Start with one meeting. Replace the slide deck with a two-page memo. Give everyone ten minutes to read it in silence. Then talk. The difference in the quality of that conversation will make the case better than anything I could write here.