Beyond the Obvious: Seeing Through the Lens of First Principles

Our brains are built to spot patterns, and that's usually helpful. But the same ability can trap us. We pay attention to what fits our beliefs and ignore what doesn't. We squeeze new information into old mental models. These shortcuts - confirmation bias, analogy-based reasoning, gut reactions - quietly shape our decisions without us noticing. First principles thinking is a way to break free from that cycle. It has significantly improved how I approach problems, and I think it can do the same for you.

What is First Principles Thinking?

The idea is simple: break a problem down to its most basic truths - things you can verify and know for certain - and build your reasoning up from there. Instead of relying on how things have always been done, you start from scratch.

This isn't new. Aristotle argued that real understanding requires identifying the fundamental elements and causes of something. During the Renaissance and Enlightenment, scientists rejected inherited wisdom and rebuilt knowledge through observation, experimentation, and rational analysis. Today, the same approach drives breakthroughs in physics, engineering, and business. The question at its core is always the same: "What do we actually know for sure?"

Why It Matters

The most famous modern example is Elon Musk and SpaceX. When Musk looked into space travel, everyone told him rockets were expensive - that's just how it was. Instead of accepting that, he broke down the cost of a rocket to its raw materials: aluminum, titanium, carbon fiber. The materials themselves weren't expensive at all. The cost came from the industry's way of doing things. By building rockets in-house from those raw materials, SpaceX cut launch costs by over 90%, fundamentally changing the space industry.

It is important to view knowledge as sort of a semantic tree - make sure you understand the fundamental principles, i.e., the trunk and big branches, before you get into the leaves/details or there is nothing for them to hang onto.

This works at smaller scales too. As an engineer, I've found that the hardest bugs aren't the complex ones - they're the ones where I'm carrying wrong assumptions. When a system behaves unexpectedly, my instinct is to reach for what worked last time. But the real fix often comes from stepping back and asking: "What is actually happening here? What do I know for certain versus what am I assuming?" Stripping away assumptions and looking at the raw facts almost always leads to a clearer, faster solution.

The Socratic method works on the same principle. Keep asking "why" until you get past the surface. Ask it five times in a row, and you'll often arrive at a root cause that was invisible at first glance.

Divide each difficulty into as many parts as is feasible and necessary to resolve it.

Why It's Hard

First principles thinking goes against how our brains naturally work. We're wired for speed - pattern matching, mental shortcuts, quick comparisons. These are useful for everyday survival, but they can block genuine understanding. Thinking from first principles requires slowing down, questioning things that seem obvious, and sitting with uncertainty for a while. It takes more effort, but the payoff is ideas and solutions that you simply can't reach by following conventional thinking.

It also benefits from drawing on multiple disciplines. Climate change, for instance, can't be understood through biology alone or economics alone - it requires combining insights from physics, chemistry, sociology, and policy. First principles thinking naturally encourages this cross-disciplinary approach because it forces you to look at what's actually true, regardless of which field that truth comes from.

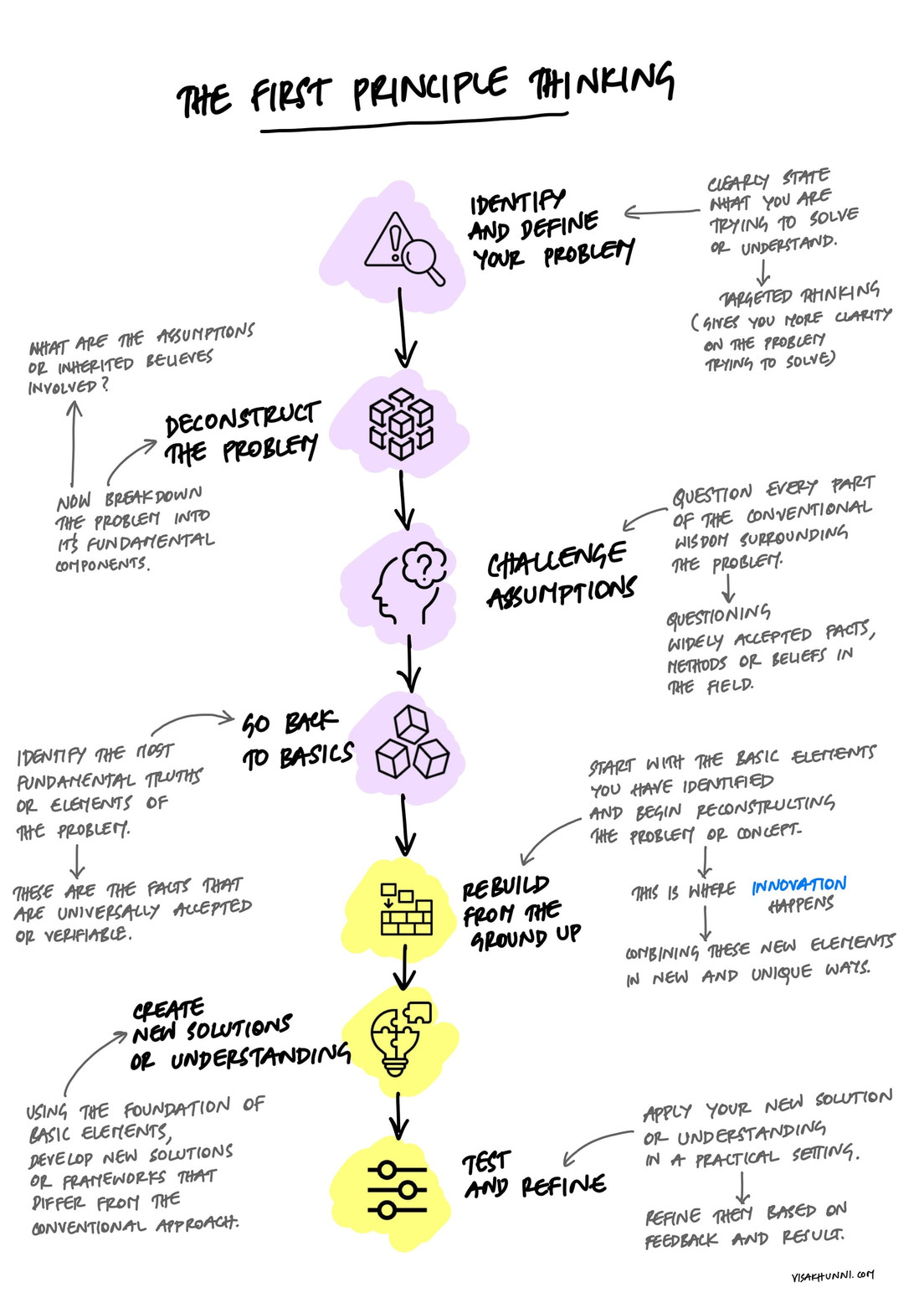

How to Apply It: Seven Steps

- Define the problem clearly. Be specific about what you're trying to solve. A vague problem leads to vague thinking.

- Break it apart. Separate what you genuinely know from what you've assumed or been told.

- Challenge every assumption. Question the "facts," the methods, and the beliefs surrounding the problem. Ask: "Is this actually true, or is it just how things have always been done?"

- Find the fundamentals. Identify the basic truths - things you can verify, test, or prove.

- Rebuild from those fundamentals. Start constructing your solution using only what you've verified. This is where original thinking happens.

- Create new solutions. With a clean foundation, you'll often find approaches that weren't visible before.

- Test and refine. Put your solution into practice, observe the results, and improve.

Practical Tips

- Be careful with analogies. They're useful for explaining ideas, but dangerous as a basis for thinking. "It's like X" can lock you into X's constraints.

- Keep asking "why." Not once - repeatedly. Each answer peels back a layer.

- Stay open to being wrong. First principles thinking often reveals that something you were sure about isn't quite right.

- Talk it through. Conversations with others expose blind spots and unexamined assumptions faster than thinking alone.

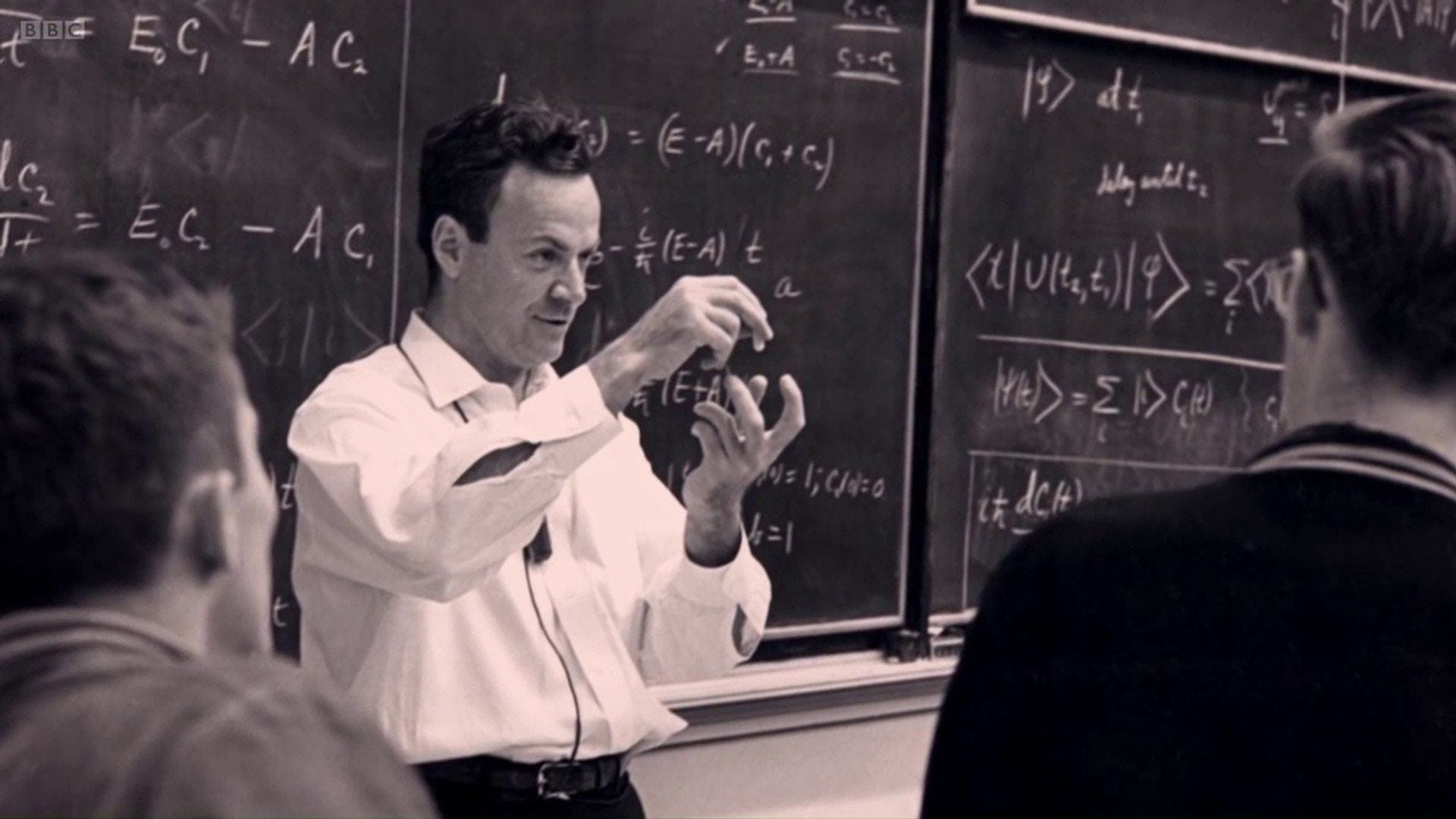

Feynman: The Great Explainer

No discussion of first principles is complete without Richard Feynman. He believed that if you can't explain something simply, you don't really understand it. His "Feynman Lectures on Physics" break down sophisticated concepts to their core, building understanding from the ground up rather than relying on memorization.

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself - and you are the easiest person to fool.

The Feynman Technique

Feynman's approach to learning is itself a first principles method. It works in four steps:

- Pick a concept you want to understand.

- Explain it in plain language, as if teaching someone with no background in the subject.

- Find the gaps - the parts where your explanation breaks down or gets vague.

- Go back, study those gaps, and simplify again.

This cycle of explain, identify gaps, and simplify forces genuine understanding. If your explanation requires jargon or hand-waving, you haven't understood it well enough yet.

Key Takeaway

First principles thinking isn't about being smarter - it's about being more honest with yourself about what you actually know versus what you've assumed. It's slower than going with your gut, but it leads to clearer thinking and more original solutions. The next time you're stuck on a problem, try this: stop looking for a similar problem someone else has solved, and instead ask yourself, "What is fundamentally true here?" You might be surprised where that question takes you.

I'll leave you with a wonderful documentary where Feynman himself demonstrates this kind of thinking - making the complex world of physics genuinely fascinating and accessible.