Beyond Goals: How OKRs Foster Growth and Innovation

I used to think measurable goals were inherently toxic. I had seen teams chase unrealistic client projects just to hit accountability targets. I had watched people promote underperforming products to meet monthly quotas. I had seen engineers stay late not because they were productive, but because "hours in office" was what got measured at appraisal time.

Then I read John Doerr's "Measure What Matters," and it reframed the whole thing for me. The problem was never measurement itself - it was what got measured, and how. Doerr lays out a framework called OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) that, when done right, does something I didn't think was possible: it makes goal-setting a tool for focus and alignment rather than a source of pressure and politics. This post is about what I learned.

What OKRs Actually Are

The idea is straightforward. An Objective is what you want to achieve - qualitative, ambitious, and clear enough that everyone understands it. Key Results are how you know you're getting there - quantitative, specific, and time-bound.

Here's a concrete example. Say you're running a team that builds an invoicing platform:

- Objective: Make the invoicing experience fast and reliable for small businesses.

- Key Result 1: Reduce average invoice generation time from 8 seconds to under 2 seconds.

- Key Result 2: Achieve 99.9% uptime over the quarter.

- Key Result 3: Reduce customer-reported billing errors by 40%.

Notice what's happening here. The objective gives direction and meaning - it tells the team why their work matters. The key results make it concrete - at the end of the quarter, you can look at each one and say yes or no, without ambiguity. There's no room for hand-waving.

The key result has to be measurable. But at the end you can look, and without any arguments: Did I do that or did I not do it? Yes? No? Simple. No judgments in it.

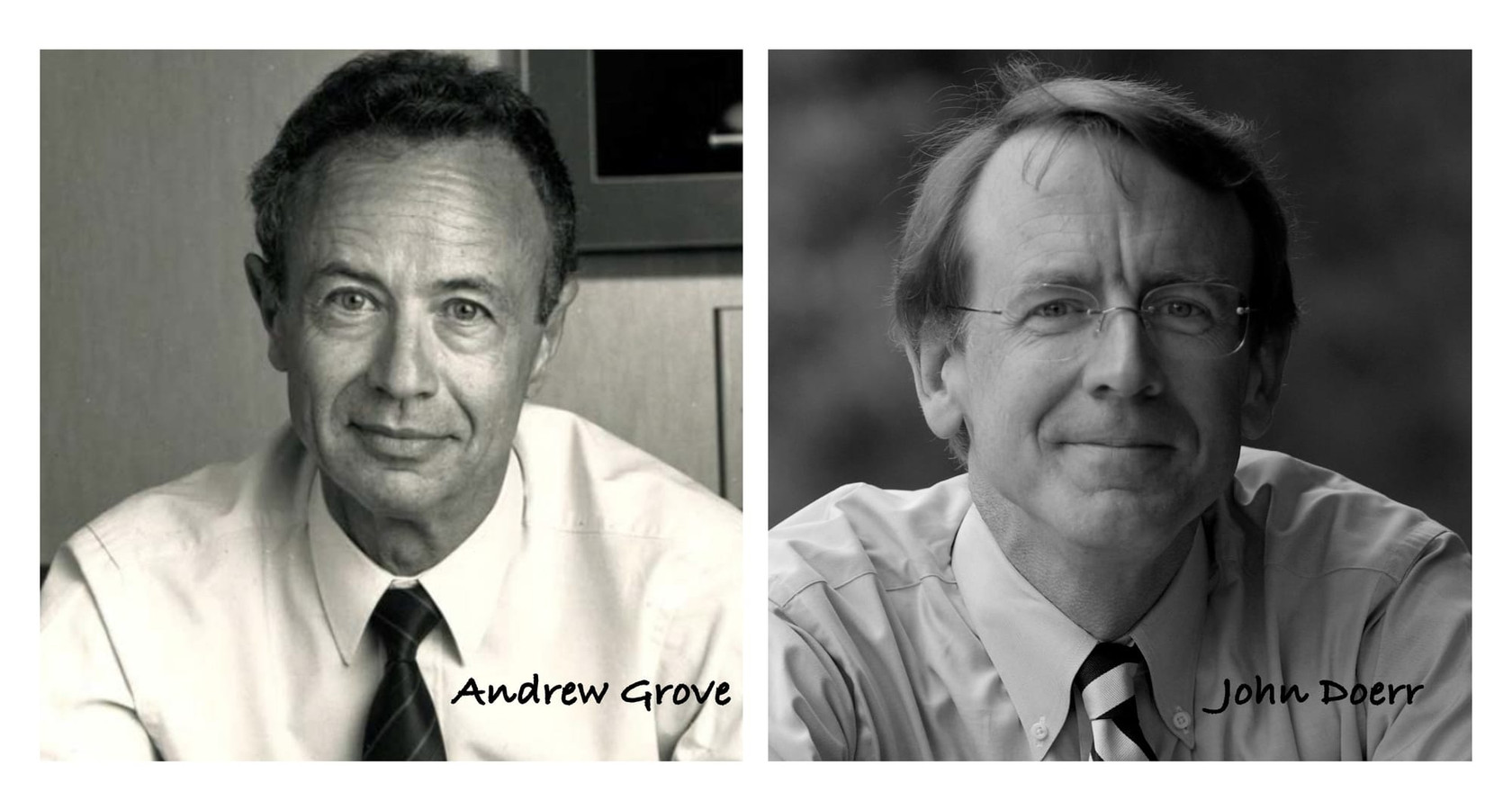

Where This Came From: Intel to Google

OKRs weren't born in a management consulting firm. They came from Andrew Grove, co-founder and CEO of Intel, in the late 1960s. Grove was an engineer by training, and he wanted a system that was rigorous without being bureaucratic - one that could keep a fast-growing company aligned without drowning people in process. He laid out the approach in his 1983 book High Output Management, which remains one of the best books on organizational effectiveness ever written.

The framework might have stayed an Intel thing if not for John Doerr. As a venture capitalist at Kleiner Perkins, Doerr had seen OKRs work firsthand at Intel. In 1999, he introduced them to a young company called Google - at the time, just a few dozen people working out of a garage. Larry Page and Sergey Brin adopted the system, and Google has used OKRs every quarter since.

OKRs have helped lead us to 10x growth, many times over. They've helped make our crazily bold mission of organizing the world's information perhaps even achievable. They've kept me and the rest of the company on time and track when it mattered the most.

Since then, the framework has spread to companies like LinkedIn, Twitter, Spotify, and the Gates Foundation. But the core mechanism is still what Grove designed at Intel: ambitious objectives, measurable results, reviewed regularly.

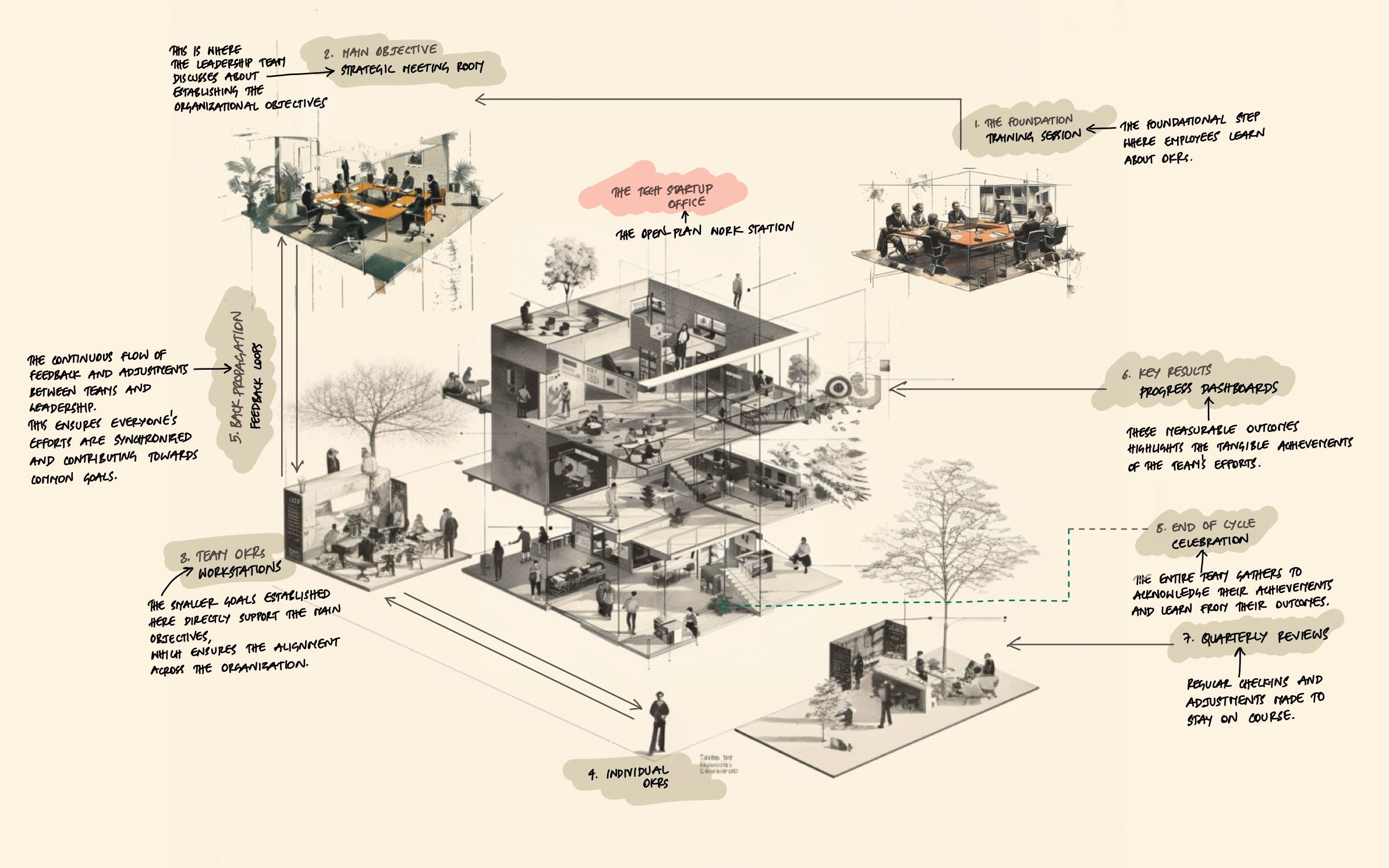

Why OKRs Work (When Done Right)

Reading Doerr's book and looking at how successful companies use OKRs, a few patterns stand out for why this framework delivers results where others don't.

Focus

Most organizations have too many priorities, which effectively means they have none. When everything is important, nothing is. OKRs force you to choose - typically 3 to 5 objectives per quarter, no more. This constraint is the feature, not a limitation. It makes teams confront the uncomfortable question: what actually matters most right now?

Alignment

In most companies, goals are set at the top and handed down. The people doing the actual work rarely see how their effort connects to the bigger picture. OKRs change this by making objectives visible across the entire organization. When a frontend engineer can see that their performance optimization work directly supports the company's objective of improving user experience, their work takes on a different meaning. They're not just closing tickets - they're contributing to something they can see and understand.

This works in both directions. Individual and team OKRs feed upward into organizational OKRs, creating a two-way flow. Leadership sets the direction, but teams have real input into how they get there. This balance between top-down direction and bottom-up ownership is what separates OKRs from traditional cascading goals.

Transparency

OKRs are meant to be public - visible to everyone in the organization. This openness does something powerful: it builds trust and eliminates the politics that come from hidden agendas. When every team's objectives are out in the open, collaboration happens naturally. You can see where your work overlaps with another team's goals, where you might be blocking someone, or where joining forces would move both teams forward faster.

It's not a key result unless it has a number.

Normalizing Ambitious Failure

This is the part that surprised me most. In the OKR framework, consistently hitting 100% of your key results is actually a warning sign - it means your objectives weren't ambitious enough. The sweet spot is around 60-70% achievement. Google explicitly encourages "stretch goals" - objectives that feel slightly uncomfortable, where falling short still means you've accomplished something meaningful.

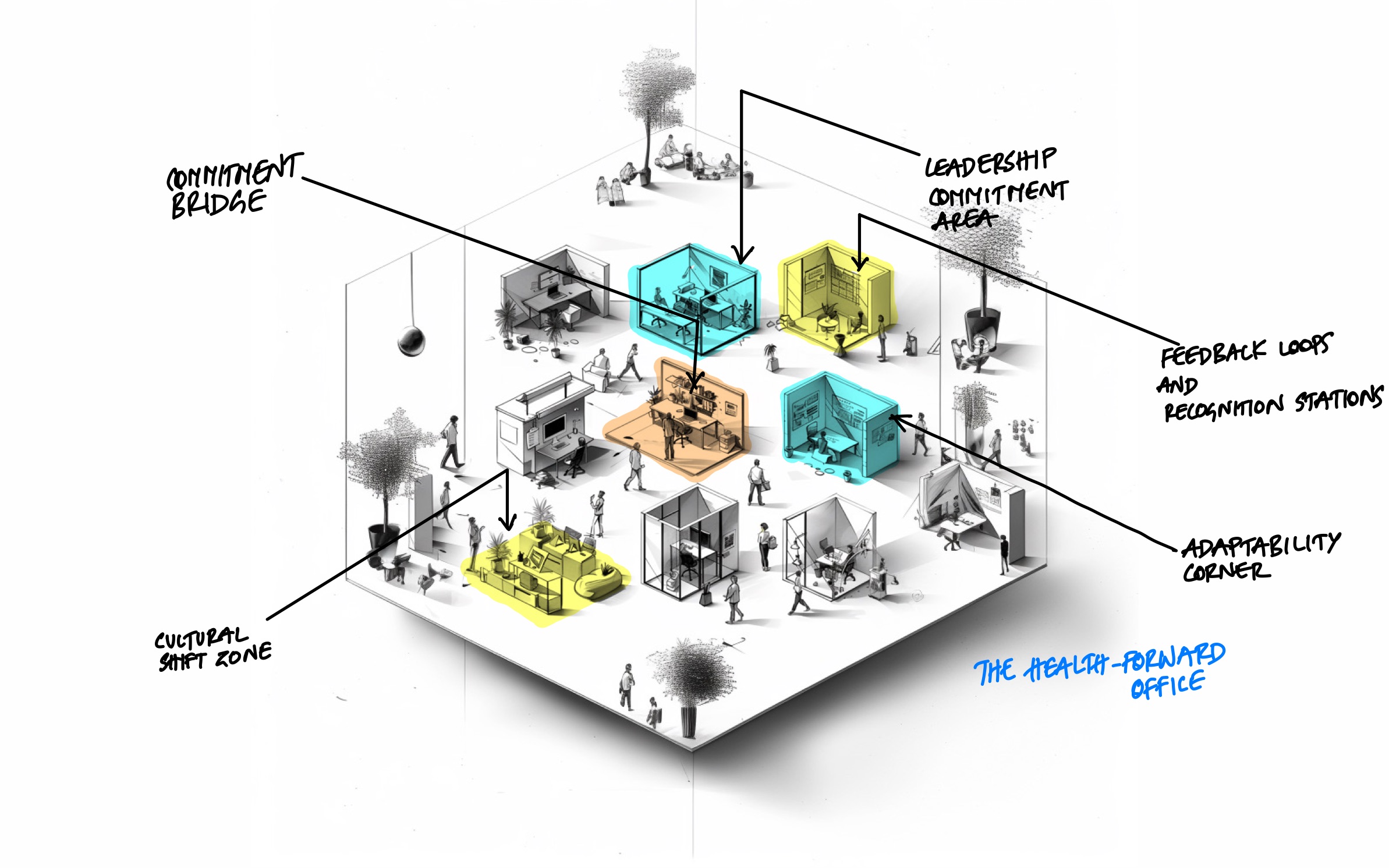

This is a cultural shift, not just a process change. When falling short of an ambitious target is expected and even celebrated, people stop sandbagging their goals. They stop playing it safe just to look good on a scorecard. Instead, they aim for things that could genuinely move the needle - knowing that partial progress on a bold objective is worth more than perfect execution of a timid one.

We never thought small. The stretch was always there. But our goals were so gigantic that we stretched too thin and got people worn out. OKRs saved us, really.

The Missing Piece: Continuous Feedback

OKRs tell you where you're going and how you'll know when you arrive. But they don't, on their own, help people grow along the way. That's where CFRs come in - Conversations, Feedback, and Recognition. Doerr argues that OKRs without CFRs are like a car without steering: you have the engine and the destination, but no way to adjust course as you drive.

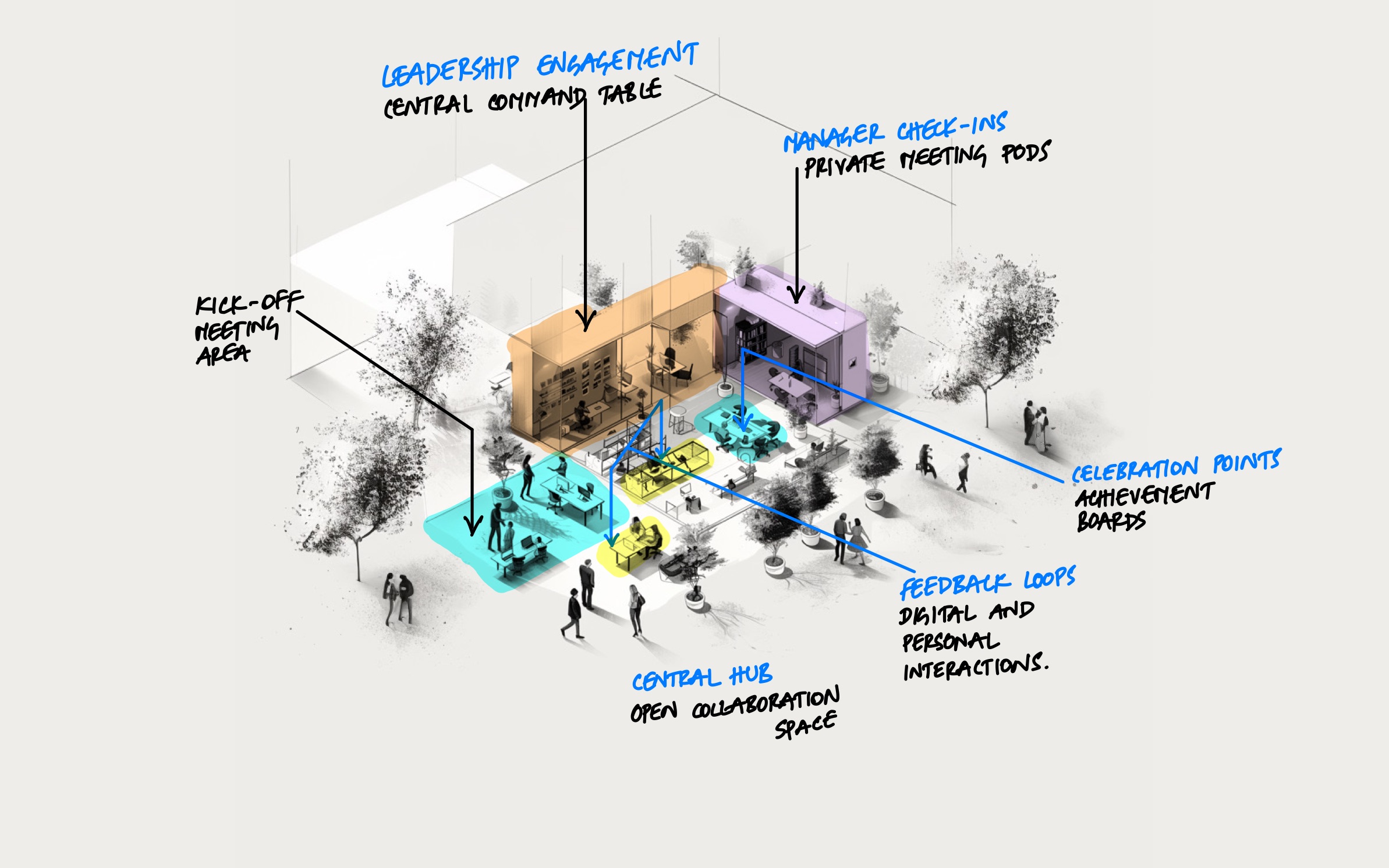

The idea is simple. Conversations are regular, lightweight check-ins between managers and team members - not annual performance reviews, but frequent discussions about progress, blockers, and development. Feedback flows in all directions - not just top-down, but peer-to-peer and bottom-up. And Recognition means acknowledging good work in the moment, not saving it for a quarterly review.

Adobe is a good example of this in practice. They moved away from annual performance reviews entirely, replacing them with a system called "Check-in" - frequent manager-employee conversations focused on expectations, feedback, and growth. The result was a measurable decrease in voluntary turnover and a significant increase in employee engagement. The key insight was that feedback is most useful when it's timely and specific, not when it arrives months after the fact in a formal review.

When CFRs work well alongside OKRs, something interesting happens. The objectives provide direction and accountability, while the continuous feedback provides the human support that makes ambitious goals feel achievable rather than threatening. People are more willing to stretch when they know someone is paying attention, offering guidance, and recognizing their effort - not just grading the outcome.

OKRs in the Real World

Theory is useful, but the real test of any framework is whether it works in practice. Here are two companies that used OKRs to drive specific, measurable results.

LinkedIn: Platform Engagement

LinkedIn set an objective to increase platform engagement - a broad goal that could easily become vague without specific key results to anchor it. Their approach:

- Objective: Increase platform engagement.

- KR1: Increase average time spent on site per user by 15%.

- KR2: Grow monthly active users by 10%.

- KR3: Raise user posts and shares by 25%.

What makes this effective is that the three key results attack the problem from different angles. Time on site measures depth. Active users measures breadth. Posts and shares measures participation. Together, they paint a complete picture of what "engagement" actually means - and they prevent the team from gaming any single metric at the expense of the others.

Intel: Market Leadership

Intel's objective was to maintain market leadership in microprocessors - a goal that required balancing innovation, efficiency, and partnerships simultaneously:

- Objective: Maintain market leadership in microprocessors.

- KR1: Launch a new processor line with 10% better performance than the nearest competitor.

- KR2: Reduce production costs by 5%.

- KR3: Secure 5 major partnerships with leading PC manufacturers.

This is a good example of how OKRs can hold competing priorities in tension. Building the best processor costs money, but reducing costs is also a key result. These aren't contradictions - they're creative constraints that force the team to find solutions that satisfy both, rather than optimizing one at the expense of the other.

Key Takeaway

Coming back to where I started - I used to see measurement as the enemy of good culture. What changed my mind wasn't just learning about OKRs as a framework. It was understanding that the problem was never goals themselves; it was goals without meaning, goals without transparency, and goals without the human infrastructure to support them.

When objectives are ambitious and clearly communicated, when key results are honest and measurable, when feedback flows continuously and recognition happens in real time - measurement stops being a source of anxiety and starts being a source of clarity. The team knows where they're headed, they can see their progress, and they have permission to aim high and fall short.

That's a fundamentally different kind of workplace than the one I was reacting against. And it starts not with better tools, but with better questions: What truly matters? How will we know we're making progress? And are we creating an environment where people can do their best work?