One-Off Admin Processes

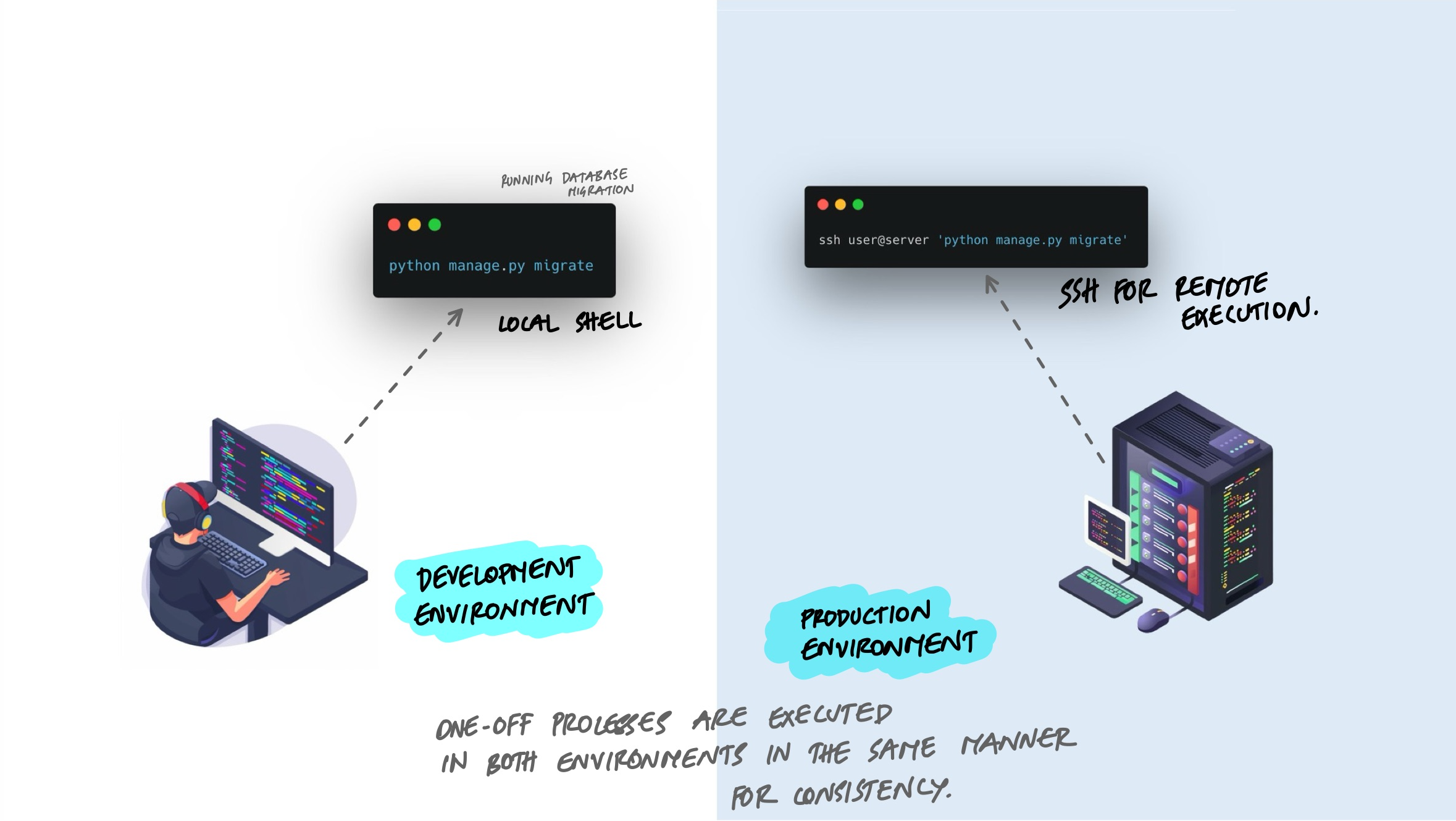

Every application needs occasional maintenance - database migrations, data cleanup, backfill jobs, one-time fixes. The temptation is to handle these as quick hacks: SSH into a server, open a database shell, run some raw SQL. But when admin tasks run with different code, different dependencies, or different configuration than the application itself, things break in ways that are hard to trace. The 12-factor methodology says these tasks should run as one-off processes using the exact same codebase and environment as the application.

What Are Admin Processes?

Admin processes are tasks that need to happen occasionally but are not part of the application's normal request-handling flow. Common examples include:

- Database migrations - adding columns, creating tables, changing indexes.

- Data fixes - correcting bad records, backfilling a new field, merging duplicate accounts.

- Interactive consoles - opening a shell to inspect data or test a function against live state.

- One-time scripts - importing data from a CSV, sending a batch notification, generating a report.

These tasks run once (or occasionally), do their job, and exit. They are not long-running web processes. But they still need access to the application's models, configuration, and database connections.

What Goes Wrong Without This Principle

When admin tasks are treated as separate from the application, several problems appear:

Raw SQL Against Production

A developer needs to fix a batch of records. Instead of writing a script in the application, they connect to the production database directly and run SQL:

# Dangerous: raw SQL bypasses application logic

psql -h prod-db -U admin -d myapp

UPDATE users SET status = 'active'

WHERE created_at < '2024-01-01'

AND status = 'pending';This skips every safeguard the application has - validation rules, audit logging, event triggers, cache invalidation. The records are updated, but nothing else in the system knows it happened. Downstream services are out of sync. There is no record of what changed or why.

Scripts That Live Outside the Repository

Someone writes a quick Python script on their laptop to fix a problem. It works. They send it to a colleague over Slack. The colleague runs it a month later, but the database schema has changed since then. The script fails or, worse, corrupts data.

Scripts that are not in the repository are not versioned, not reviewed, and not kept in sync with the application code they depend on.

Different Environment, Different Results

An admin script runs on a developer's laptop against production data. But the developer has a different Python version, different library versions, and a local .env file with stale configuration. The script behaves differently than it would in the actual production environment. Bugs surface in production that could not be reproduced locally.

The Rule: Same Code, Same Config, Same Environment

The 12-factor principle is straightforward: admin processes should run against a release, using the same codebase and configuration as any process running in that release. This means:

- Admin scripts live in the application repository, not on someone's laptop.

- They use the same database models, the same ORM, the same validation logic as the web application.

- They run with the same environment variables and dependency versions as the deployed application.

- They ship with the same release and are versioned alongside the code they operate on.

Database Migrations

Migrations are the most common admin process. They change the database schema to match what the application code expects. In Django, this looks like:

# Generate a migration from model changes

python manage.py makemigrations

# Apply pending migrations to the database

python manage.py migrateThe migration files live in the repository. They are reviewed in pull requests. They run in the same environment as the application. When you deploy a new release, you run migrate as part of the deployment process. The same migration runs in development, staging, and production - different databases, same code.

Data Fix Scripts: Management Commands

When you need to fix data, the right approach is to write a management command (or equivalent) inside the application. This gives you access to the application's models, validation, and configuration without bypassing any of them.

Here is a Django management command that deactivates users who have not logged in for over a year:

# myapp/management/commands/deactivate_stale_users.py

from django.core.management.base import BaseCommand

from django.utils import timezone

from datetime import timedelta

from myapp.models import User

class Command(BaseCommand):

help = "Deactivate users who have not logged in for over a year"

def add_arguments(self, parser):

parser.add_argument(

"--dry-run",

action="store_true",

help="Show what would be changed without making changes",

)

def handle(self, *args, **options):

cutoff = timezone.now() - timedelta(days=365)

stale = User.objects.filter(

last_login__lt=cutoff,

is_active=True,

)

self.stdout.write(f"Found {stale.count()} stale users")

if options["dry_run"]:

self.stdout.write("Dry run - no changes made")

return

updated = stale.update(is_active=False)

self.stdout.write(f"Deactivated {updated} users")Run it with:

# Preview what would happen

python manage.py deactivate_stale_users --dry-run

# Execute for real

python manage.py deactivate_stale_usersCompare this to the raw SQL approach. The management command uses the application's ORM, respects model logic, supports a dry-run flag for safety, logs what it does, and lives in the repository where it can be reviewed and versioned. If someone needs to run a similar fix six months later, the command is still there, still compatible with the current schema.

Interactive Consoles

Sometimes you need to explore data or test a hypothesis interactively. The right way is to use the application's built-in console, which loads the full application context:

# Django shell - has access to all models and settings

python manage.py shell

# Inside the shell

from myapp.models import Order

# Check how many orders are stuck in processing

Order.objects.filter(status="processing").count()

# Inspect a specific order

order = Order.objects.get(id=12345)

print(order.status, order.created_at, order.total)The shell connects to the same database with the same credentials as the running application. It uses the same model definitions. If a field was renamed last week, the shell reflects that. There is no drift between what the console sees and what the application sees.

Running Admin Tasks in Containers

In containerized environments, admin tasks should run inside a container built from the same image as the application. This guarantees the same code, same dependencies, and same configuration.

With Docker, you can run a one-off command against a running container:

# Run migration inside the running container

docker exec myapp-container python manage.py migrate

# Open an interactive shell

docker exec -it myapp-container python manage.py shell

# Run a one-off data fix

docker exec myapp-container python manage.py deactivate_stale_usersWith Kubernetes, you use a Job to run the task as a separate pod with the same image:

# k8s-migration-job.yml

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: migrate-db

spec:

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: migrate

image: myapp:v2.3.1 # same image as the deployment

command: ["python", "manage.py", "migrate"]

envFrom:

- secretRef:

name: myapp-secrets # same config as the deployment

restartPolicy: NeverThe key detail is image: myapp:v2.3.1 - the Job uses the exact same Docker image as the running deployment. Same code, same dependencies. The envFrom pulls the same environment variables. The migration runs in the same context as the web application, just as a different command.

Making Admin Tasks Safe

Admin tasks touch production data. A few practices make them safer:

- Dry-run flags. Let the script report what it would do before actually doing it. Review the output, then run again without the flag.

- Idempotent operations. If a script is safe to run twice, it is safe to retry after a failure. Check whether the work is already done before doing it.

- Batch processing with limits. Instead of updating a million records in one statement, process them in batches. This avoids long-running database locks and makes the operation easier to monitor and stop.

- Logging. Every admin script should log what it did - how many records were affected, what changed, whether it succeeded or failed. This creates an audit trail.

# Process records in batches instead of all at once

BATCH_SIZE = 500

while True:

batch = User.objects.filter(

needs_migration=True

)[:BATCH_SIZE]

if not batch:

break

for user in batch:

user.migrate_profile()

user.needs_migration = False

user.save()

logger.info(f"Migrated batch of {len(batch)} users")Key Takeaway

Admin tasks are part of your application. They should live in the repository, use the same models and configuration, and run in the same environment as the deployed application. Do not SSH into a server and run raw SQL. Do not keep scripts on someone's laptop. Write management commands, ship them with the release, and run them as one-off processes against the same code that is handling production traffic. The task runs, does its job, and exits. The codebase stays unified, the data stays consistent, and there is a clear record of what happened.