On Dependency Management

When applications depend on libraries that are installed globally on a machine, things work until they do not. Two projects need different versions of the same library. A deployment fails because someone updated a system package. A new developer clones the repository and nothing runs because half the dependencies were never documented. The 12-factor methodology captures the fix in two rules: explicitly declare all dependencies, and isolate them so nothing leaks in from the surrounding system.

The Two Rules

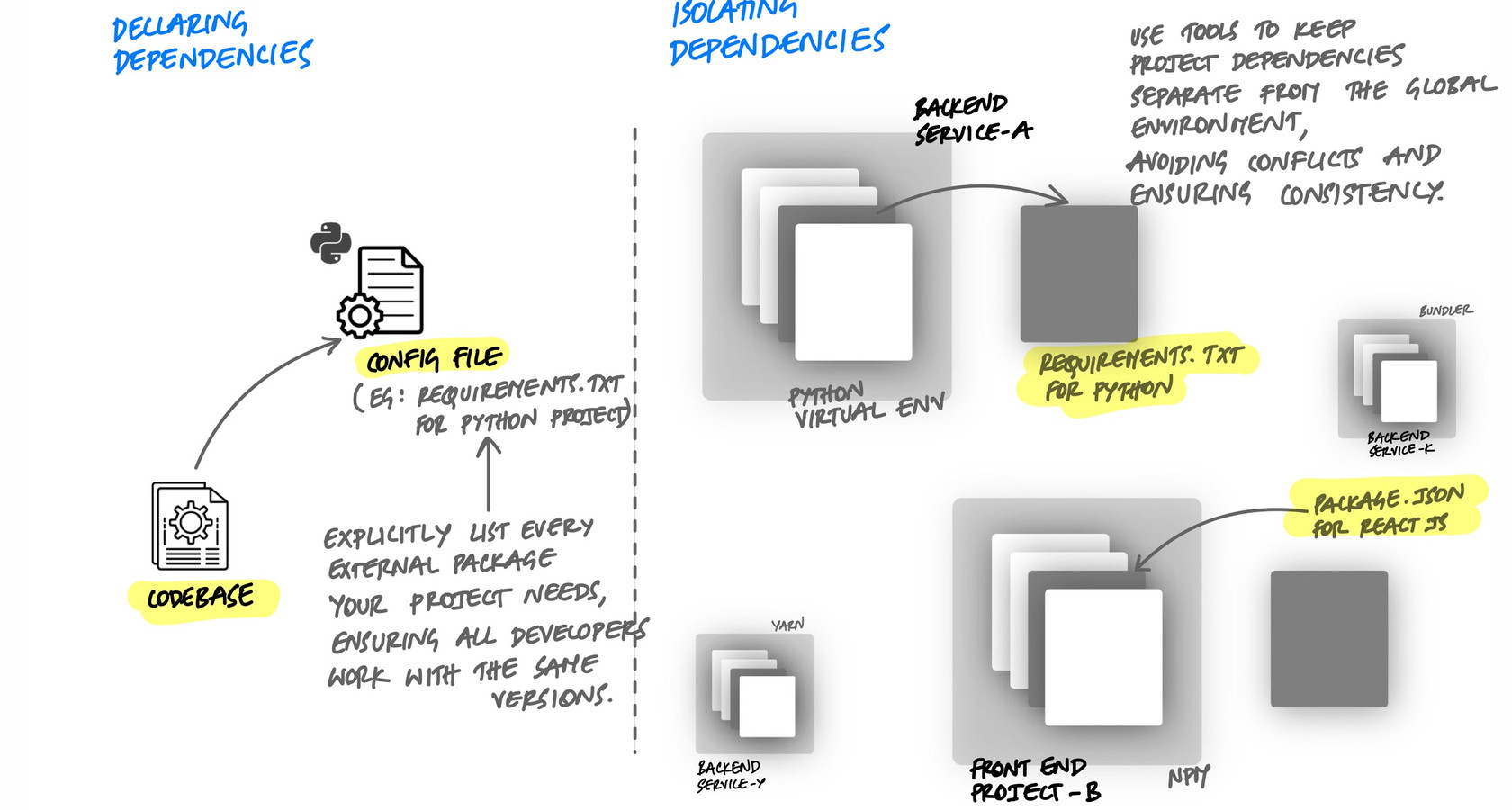

The 12-factor dependency principle has two parts:

- Declaration. Every dependency your application needs must be listed in a manifest file. Nothing is assumed to be pre-installed.

- Isolation. The application must not rely on system-wide packages. Dependencies are installed into an isolated environment so only what is declared is available.

Declaration tells you what the application needs. Isolation ensures that only what is declared is present. Together, they make the application portable and reproducible.

What Breaks Without Explicit Dependencies

When dependencies are not declared explicitly, problems show up in predictable ways:

The "Works on My Machine" Problem

A developer installs a library globally to try it out. It works. They commit the code but forget to add the library to the requirements file. On their machine, everything passes. In CI or on a colleague's machine, the import fails:

# This fails on any machine that doesn't have requests installed globally

import requests

response = requests.get("https://api.example.com/data")

# ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'requests'The fix is obvious once you know the library is missing, but the failure might not be this clear. It could surface as an obscure error deep in a call stack, and debugging it wastes time that proper declaration would have prevented.

Version Conflicts Between Projects

Project A needs SQLAlchemy 1.4. Project B needs SQLAlchemy 2.0. If both install into the global Python environment, only one version can exist at a time. Installing dependencies for Project B breaks Project A. This is a direct consequence of not isolating dependencies per project.

Implicit System Dependencies

The application calls curl from a subprocess, or depends on libpq for PostgreSQL connections, or uses ImageMagick to resize images. These are not Python packages - they are system-level tools. If they are not documented, the application works on the developer's machine (where they happen to be installed) and fails everywhere else.

Declaring Dependencies

In Python, the standard way to declare dependencies is a requirements file. Every library the application imports should be listed with a pinned version:

# requirements.txt

flask==3.0.0

sqlalchemy==2.0.23

redis==5.0.1

celery==5.3.6

gunicorn==21.2.0Pinning versions matters. Without pinned versions, running pip install -r requirements.txt today and tomorrow could produce different results if a library releases a new version in between. A deploy that worked yesterday breaks today, and nothing in your code changed. Pinned versions make builds reproducible.

Lock Files: Pinning the Entire Dependency Tree

Pinning your direct dependencies is a good start, but your dependencies have dependencies of their own. Flask 3.0.0 depends on Werkzeug, Jinja2, Click, and others. If you do not pin those transitive dependencies, they can change between installs.

A lock file captures the exact version of every package in the entire dependency tree - direct and transitive:

# Generate a lock file from your current environment

pip freeze > requirements-lock.txt

# requirements-lock.txt (every package, exact versions)

blinker==1.7.0

celery==5.3.6

click==8.1.7

flask==3.0.0

itsdangerous==2.1.2

jinja2==3.1.2

markupsafe==2.1.3

redis==5.0.1

sqlalchemy==2.0.23

werkzeug==3.0.1

# ... every transitive dependency listedNow every install produces the exact same environment. The lock file is committed to the repository. When you deploy, you install from the lock file, not from the loose requirements. This is what makes builds truly reproducible.

Tools like pip-tools or Poetry automate this. You declare your direct dependencies in one file, and the tool generates a lock file with the full resolved tree:

# With pip-tools

# requirements.in - what you declare (direct dependencies)

flask==3.0.0

sqlalchemy==2.0.23

redis==5.0.1

# Compile the lock file

pip-compile requirements.in -o requirements.txt

# Install from the lock file (exact versions, every time)

pip-sync requirements.txtIsolating Dependencies with Virtual Environments

Declaring dependencies tells you what is needed. Isolation ensures that only those packages are available. In Python, virtual environments provide this isolation:

# Create a virtual environment

python -m venv .venv

# Activate it

source .venv/bin/activate

# Install only the declared dependencies

pip install -r requirements.txt

# Now only these packages are available to the application

pip list

# flask 3.0.0

# sqlalchemy 2.0.23

# redis 5.0.1

# ... (only declared packages and their dependencies)Without a virtual environment, pip install puts packages into the global Python environment. Every project on the machine shares the same packages. With a virtual environment, each project has its own isolated set of packages. Project A can use SQLAlchemy 1.4 while Project B uses SQLAlchemy 2.0 on the same machine with no conflict.

Isolation also catches missing declarations. If you forget to add a library to requirements.txt, it will not be in the virtual environment, and your code will fail immediately rather than silently relying on a globally installed copy.

System-Level Dependencies

Not all dependencies are Python packages. Some are system tools or C libraries that Python packages depend on:

psycopg2needslibpq(the PostgreSQL client library)Pillowneedslibjpegandzlibfor image processing- A subprocess call to

ffmpegorwkhtmltopdfrequires those tools to be installed

Virtual environments do not handle these. A pip install for psycopg2 will fail if libpq is not on the system. The 12-factor principle says a twelve-factor app never relies on the implicit existence of system-wide packages. These system dependencies need to be documented, and ideally managed through infrastructure tooling.

This is one of the reasons containers became the standard. A Dockerfile can declare both Python packages and system packages in one place:

FROM python:3.12-slim

# System-level dependencies - documented and reproducible

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y \

libpq-dev \

libjpeg-dev \

&& rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

WORKDIR /app

# Python dependencies - declared and pinned

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

COPY . .

CMD ["gunicorn", "--bind", "0.0.0.0:5000", "app:app"]Now every dependency - Python libraries and system packages - is declared in version-controlled files. Anyone can build the image and get the exact same environment. No surprises.

The Complete Setup: Clone to Running

When dependencies are declared and isolated properly, a new developer should be able to go from cloning the repository to running the application with a few deterministic commands:

# Clone the repository

git clone https://github.com/myorg/myapp.git

cd myapp

# Create and activate a virtual environment

python -m venv .venv

source .venv/bin/activate

# Install all declared dependencies

pip install -r requirements.txt

# Run the application

python app.pyNo hunting for undocumented packages. No guessing which version to install. No asking a colleague what they have on their machine. The requirements file is the single source of truth.

With Docker, the setup is even simpler:

git clone https://github.com/myorg/myapp.git

cd myapp

docker compose upOne command, and every dependency - Python packages, system libraries, the exact Python version - is handled. This is the end goal of proper dependency management: the application works the same way on every machine, every time.

Key Takeaway

Declare every dependency explicitly. Pin versions so builds are reproducible. Use lock files to capture the full dependency tree. Isolate dependencies with virtual environments so nothing leaks in from the global system. Document system-level dependencies, or better yet, use containers to declare everything in one place. When this is done right, any developer can clone the repository and have a working application in minutes. When it is not, every new machine is a mystery and every deploy is a gamble.